2.1 - Inference for the Population Intercept and Slope

2.1 - Inference for the Population Intercept and SlopeRecall that we are ultimately always interested in drawing conclusions about the population, not the particular sample we observed. In the simple regression setting, we are often interested in learning about the population intercept \(\beta_{0}\) and the population slope \(\beta_{1}\). As you know, confidence intervals and hypothesis tests are two related, but different, ways of learning about the values of population parameters. Here, we will learn how to calculate confidence intervals and conduct hypothesis tests for both \(\beta_{0}\) and \(\beta_{1}\).

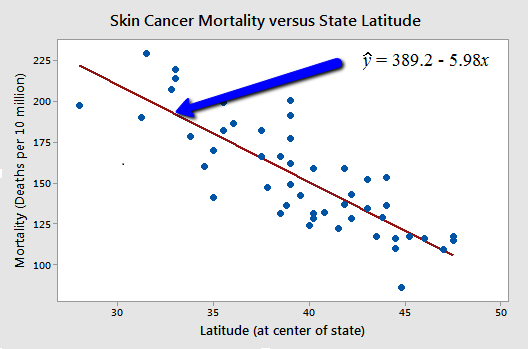

Let's revisit the example concerning the relationship between skin cancer mortality and state latitude (Skin Cancer data). The response variable y is the mortality rate (number of deaths per 10 million people) of white males due to malignant skin melanoma from 1950-1959. The predictor variable x is the latitude (degrees North) at the center of each of the 49 states in the United States. A subset of the data looks like this:

|

#

|

State

|

Latitude

|

Mortality

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

1

|

Alabama

|

33.0

|

219

|

|

2

|

Arizona

|

34.5

|

160

|

|

3

|

Arkansas

|

35.0

|

170

|

|

4

|

California

|

37.5

|

182

|

|

5

|

Colorado

|

39.0

|

149

|

|

\(\vdots\)

|

\(\vdots\) |

\(\vdots\)

|

\(\vdots\)

|

|

49

|

Wyoming

|

43.0

|

134

|

and a plot of the data with the estimated regression equation looks like this:

Is there a relationship between state latitude and skin cancer mortality? Certainly, since the estimated slope of the line, b1, is -5.98, not 0, there is a relationship between state latitude and skin cancer mortality in the sample of 49 data points. But, we want to know if there is a relationship between the population of all the latitudes and skin cancer mortality rates. That is, we want to know if the population slope \(\beta_{1}\)is unlikely to be 0.

(1-\(\alpha\))100% t-interval for the slope parameter \(\beta_{1}\)

- Confidence Interval for \(\beta_{1}\)

-

The formula for the confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\), in words, is:

Sample estimate ± (t-multiplier × standard error)

and, in notation, is:

\(b_1 \pm t_{(\alpha/2, n-2)}\times \left( \dfrac{\sqrt{MSE}}{\sqrt{\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2}} \right)\)

The resulting confidence interval not only gives us a range of values that is likely to contain the true unknown value \(\beta_{1}\). It also allows us to answer the research question "is the predictor x linearly related to the response y?" If the confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\) contains 0, then we conclude that there is no evidence of a linear relationship between the predictor x and the response y in the population. On the other hand, if the confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\)does not contain 0, then we conclude that there is evidence of a linear relationship between the predictor x and the response y in the population.

An \(\alpha\)-level hypothesis test for the slope parameter \(\beta_{1}\)

We follow standard hypothesis test procedures in conducting a hypothesis test for the slope \(\beta_{1}\). First, we specify the null and alternative hypotheses:

- Null hypothesis \(H_{0} \colon \beta_{1}\)= some number \(\beta\)

- Alternative hypothesis \(H_{A} \colon \beta_{1}\)≠ some number \(\beta\)

The phrase "some number \(\beta\)" means that you can test whether or not the population slope takes on any value. Most often, however, we are interested in testing whether \(\beta_{1}\) is 0. By default, Minitab conducts the hypothesis test with the null hypothesis, \(\beta_{1}\) is equal to 0, and the alternative hypothesis, \(\beta_{1}\)is not equal to 0. However, we can test values other than 0 and the alternative hypothesis can also state that \(\beta_{1}\) is less than (<) some number \(\beta\) or greater than (>) some number \(\beta\).

Second, we calculate the value of the test statistic using the following formula:

Third, we use the resulting test statistic to calculate the P-value. As always, the P-value is the answer to the question "how likely is it that we’d get a test statistic t* as extreme as we did if the null hypothesis were true?" The P-value is determined by referring to a t-distribution with n-2 degrees of freedom.

Finally, we make a decision:

- If the P-value is smaller than the significance level \(\alpha\), we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative. We conclude that "there is sufficient evidence at the \(\alpha\) level to conclude that there is a linear relationship in the population between the predictor x and response y."

- If the P-value is larger than the significance level \(\alpha\), we fail to reject the null hypothesis. We conclude "there is not enough evidence at the \(\alpha\) level to conclude that there is a linear relationship in the population between the predictor x and response y."

Minitab®

Drawing conclusions about the slope parameter \(\beta_{1}\) using Minitab

Let's see how we can use Minitab to calculate confidence intervals and conduct hypothesis tests for the slope \(\beta_{1}\). Minitab's regression analysis output for our skin cancer mortality and latitude example appears below.

The line pertaining to the latitude predictor, Lat, in the summary table of predictors has been bolded. It tells us that the estimated slope coefficient \(b_{1}\), under the column labeled Coef, is -5.9776. The estimated standard error of \(b_{1}\), denoted se(\(b_{1}\)), in the column labeled SE Coef for "standard error of the coefficient," is 0.5984.

Analysis of Variance

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1 | 36464 | 36464 | 98.80 | 0.000 |

| Residual Error | 47 | 17173 | 365 | ||

| Total | 48 | 53637 |

Coefficients

| Predictor | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 389.19 | 23.81 | 16.34 | 0.000 |

| Lat | -5.9776 | 0.5984 | -9.99 | 0.000 |

Model Summary

| S | R-sq | R-sq(adj) |

|---|---|---|

| 19.12 | 68.0% | 67.3% |

The Regression equation

Mort = 389 - 5.98 Lat

By default, the test statistic is calculated assuming the user wants to test that the slope is 0. Dividing the estimated coefficient of -5.9776 by the estimated standard error of 0.5984, Minitab reports that the test statistic T is -9.99.

By default, the P-value is calculated assuming the alternative hypothesis is a "two-tailed, not-equal-to" hypothesis. Upon calculating the probability that a t-random variable with n-2 = 47 degrees of freedom would be larger than 9.99, and multiplying the probability by 2, Minitab reports that P is 0.000 (to three decimal places). That is, the P-value is less than 0.001. (Note we multiply the probability by 2 since this is a two-tailed test.)

Because the P-value is so small (less than 0.001), we can reject the null hypothesis and conclude that \(\beta_{1}\) does not equal 0. There is sufficient evidence, at the \(\alpha\) = 0.05 level, to conclude that there is a linear relationship in the population between skin cancer mortality and latitude.

It's easy to calculate a 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\) using the information in the Minitab output. You just need to use Minitab to find the t-multiplier for you. It is \(t_{\left(0.025, 47\right)} = 2.0117\). Then, the 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\)is \(-5.9776 ± 2.0117(0.5984) \) or (-7.2, -4.8). (Alternatively, Minitab can display the interval directly if you click the "Results" tab in the Regression dialog box, select "Expanded Table" and check "Coefficients.")

We can be 95% confident that the population slope is between -7.2 and -4.8. That is, we can be 95% confident that for every additional one-degree increase in latitude, the mean skin cancer mortality rate decreases between 4.8 and 7.2 deaths per 10 million people.

Video: Using Minitab for the Slope Test

Factors affecting the width of a confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\)

Recall that, in general, we want our confidence intervals to be as narrow as possible. If we know what factors affect the length of a confidence interval for the slope \(\beta_{1}\), we can control them to ensure that we obtain a narrow interval. The factors can be easily determined by studying the formula for the confidence interval:

First, subtracting the lower endpoint of the interval from the upper endpoint of the interval, we determine that the width of the interval is:

So, how can we affect the width of our resulting interval for \(\beta_{1}\)?

-

As the confidence level decreases, the width of the interval decreases. Therefore, if we decrease our confidence level, we decrease the width of our interval. Clearly, we don't want to decrease the confidence level too much. Typically, confidence levels are never set below 90%.

-

As MSE decreases, the width of the interval decreases. The value of MSE depends on only two factors — how much the responses vary naturally around the estimated regression line, and how well your regression function (line) fits the data. Clearly, you can't control the first factor all that much other than to ensure that you are not adding any unnecessary error in your measurement process. Throughout this course, we'll learn ways to make sure that the regression function fits the data as well as it can.

-

The more spread out the predictor x values, the narrower the interval. The quantity \(\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2\) in the denominator summarizes the spread of the predictor x values. The more spread out the predictor values, the larger the denominator, and hence the narrower the interval. Therefore, we can decrease the width of our interval by ensuring that our predictor values are sufficiently spread out.

-

As the sample size increases, the width of the interval decreases. The sample size plays a role in two ways. First, recall that the t-multiplier depends on the sample size through n-2. Therefore, as the sample size increases, the t-multiplier decreases, and the length of the interval decreases. Second, the denominator \(\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2\) also depends on n. The larger the sample size, the more terms you add to this sum, the larger the denominator, and the narrower the interval. Therefore, in general, you can ensure that your interval is narrow by having a large enough sample.

Six possible outcomes concerning slope \(\beta_{1}\)

There are six possible outcomes whenever we test whether there is a linear relationship between the predictor x and the response y, that is, whenever we test the null hypothesis \(H_{0} \colon \beta_{1}\) = 0 against the alternative hypothesis \(H_{A} \colon \beta_{1} ≠ 0\).

When we don't reject the null hypothesis, \(H_{0} \colon \beta_{1} = 0\), any of the following three realities are possible:

- We committed a Type II error. That is, in reality \(\beta_{1} ≠ 0\) and our sample data just didn't provide enough evidence to conclude that \(\beta_{1}\)≠ 0.

- There really is not much of a linear relationship between x and y.

- There is a relationship between x and y — it is just not linear.

When we do reject the null hypothesis, \(H_{0} \colon \beta_{1}\)= 0 in favor of the alternative hypothesis \(H_{A} \colon \beta_{1}\)≠ 0, any of the following three realities are possible:

- We committed a Type I error. That is, in reality \(\beta_{1} = 0\), but we have an unusual sample that suggests that \(\beta_{1} ≠ 0\).

- The relationship between x and y is indeed linear.

- A linear function fits the data, okay, but a curved ("curvilinear") function would fit the data even better.

(1-\(\alpha\))100% t-interval for intercept parameter \(\beta_{0}\)

Calculating confidence intervals and conducting hypothesis tests for the intercept parameter \(\beta_{0}\) is not done as often as it is for the slope parameter \(\beta_{1}\). The reason for this becomes clear upon reviewing the meaning of \(\beta_{0}\). The intercept parameter \(\beta_{0}\) is the mean of the responses at x = 0. If x = 0 is meaningless, as it would be, for example, if your predictor variable was height, then \(\beta_{0}\) is not meaningful. For the sake of completeness, we present the methods here for those situations in which \(\beta_{0}\) is meaningful.

- Confidence Interval for \(\beta_{0}\)

-

The formula for the confidence interval for \(\beta_{0}\), in words, is:

Sample estimate ± (t-multiplier × standard error)

and, in notation, is:

\(b_0 \pm t_{\alpha/2, n-2} \times \sqrt{MSE} \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{\bar{x}^2}{\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2}}\)

The resulting confidence interval gives us a range of values that is likely to contain the true unknown value \(\beta_{0}\). The factors affecting the length of a confidence interval for \(\beta_{0}\) are identical to the factors affecting the length of a confidence interval for \(\beta_{1}\).

An \(\alpha\)-level hypothesis test for intercept parameter \(\beta_{0}\)

Again, we follow standard hypothesis test procedures. First, we specify the null and alternative hypotheses:

- Null hypothesis \(H_{0}\): \(\beta_{0}\) = some number \(\beta\)

- Alternative hypothesis \(H_{A}\): \(\beta_{0}\) ≠ some number \(\beta\)

The phrase "some number \(\beta\)" means that you can test whether or not the population intercept takes on any value. By default, Minitab conducts the hypothesis test for testing whether or not \(\beta_{0}\) is 0. But, the alternative hypothesis can also state that \(\beta_{0}\) is less than (<) some number \(\beta\) or greater than (>) some number \(\beta\).

Second, we calculate the value of the test statistic using the following formula:

\(t^*=\dfrac{b_0-\beta}{\sqrt{MSE} \sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}+\dfrac{\bar{x}^2}{\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2}}}=\dfrac{b_0-\beta}{se(b_0)}\)

Third, we use the resulting test statistic to calculate the P-value. Again, the P-value is the answer to the question "how likely is it that we’d get a test statistic t* as extreme as we did if the null hypothesis were true?" The P-value is determined by referring to a t-distribution with n-2 degrees of freedom.

Finally, we make a decision. If the P-value is smaller than the significance level \(\alpha\), we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative. If we conduct a "two-tailed, not-equal-to-0" test, we conclude "there is sufficient evidence at the \(\alpha\) level to conclude that the mean of the responses is not 0 when x = 0." If the P-value is larger than the significance level \(\alpha\), we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Minitab®

Drawing conclusions about intercept parameter \(\beta_{0}\) using Minitab

Let's see how we can use Minitab to calculate confidence intervals and conduct hypothesis tests for the intercept \(\beta_{0}\). Minitab's regression analysis output for our skin cancer mortality and latitude example appears below. The work involved is very similar to that for the slope \(\beta_{1}\).

The line pertaining to the intercept, which Minitab always refers to as Constant, in the summary table of predictors has been bolded. It tells us that the estimated intercept coefficient \(b_{0}\), under the column labeled Coef, is 389.19. The estimated standard error of \(b_{0}\), denoted se(\(b_{0}\)), in the column labeled SE Coef is 23.81.

Analysis of Variance

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1 | 36464 | 36464 | 98.80 | 0.000 |

| Residual Error | 47 | 17173 | 365 | ||

| Total | 48 | 53637 |

Model Summary

| S | R-sq | R-sq(adj) |

|---|---|---|

| 19.12 | 68.0% | 67.3% |

Coefficients

| Predictor | Coef | SE Coef | T-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 389.19 | 23.81 | 16.34 | 0.000 |

| Lat | -5.9776 | 0.5984 | -9.99 | 0.000 |

Regression Equation

Mort = 389 - 5.98 Lat

By default, the test statistic is calculated assuming the user wants to test that the mean response is 0 when x = 0. Note that this is an ill-advised test here because the predictor values in the sample do not include a latitude of 0. That is, such a test involves extrapolating outside the scope of the model. Nonetheless, for the sake of illustration, let's proceed to assume that it is an okay thing to do.

Dividing the estimated coefficient of 389.19 by the estimated standard error of 23.81, Minitab reports that the test statistic T is 16.34. By default, the P-value is calculated assuming the alternative hypothesis is a "two-tailed, not-equal-to-0" hypothesis. Upon calculating the probability that a t random variable with n-2 = 47 degrees of freedom would be larger than 16.34, and multiplying the probability by 2, Minitab reports that P is 0.000 (to three decimal places). That is, the P-value is less than 0.001.

Because the P-value is so small (less than 0.001), we can reject the null hypothesis and conclude that \(\beta_{0}\) does not equal 0 when x = 0. There is sufficient evidence, at the \(\alpha\) = 0.05 level, to conclude that the mean mortality rate at a latitude of 0 degrees North is not 0. (Again, note that we have to extrapolate in order to arrive at this conclusion, which in general is not advisable.)

Proceed as previously described to calculate a 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_{0}\). Use Minitab to find the t-multiplier for you. Again, it is \(t_{\left(0.025, 47\right)} = 2.0117 \). Then, the 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_{0}\) is \(389.19 ± 2.0117\left(23.81\right) = \left(341.3, 437.1\right) \). (Alternatively, Minitab can display the interval directly if you click the "Results" tab in the Regression dialog box, select "Expanded Table" and check "Coefficients.") We can be 95% confident that the population intercept is between 341.3 and 437.1. That is, we can be 95% confident that the mean mortality rate at a latitude of 0 degrees North is between 341.3 and 437.1 deaths per 10 million people. (Again, it is probably not a good idea to make this claim because of the severe extrapolation involved.)

Statistical inference conditions

We've made no mention yet of the conditions that must be true in order for it to be okay to use the above confidence interval formulas and hypothesis testing procedures for \(\beta_{0}\) and \(\beta_{1}\). In short, the "LINE" assumptions we discussed earlier — linearity, independence, normality, and equal variance — must hold. It is not a big deal if the error terms (and thus responses) are only approximately normal. If you have a large sample, then the error terms can even deviate somewhat far from normality.

Regression Through the Origin (RTO)

In rare circumstances, it may make sense to consider a simple linear regression model in which the intercept, \(\beta_{0}\), is assumed to be exactly 0. For example, suppose we have data on the number of items produced per hour along with the number of rejects in each of those time spans. If we have a period where no items were produced, then there are obviously 0 rejects. Such a situation may indicate deleting \(\beta_{0}\) from the model since \(\beta_{0}\) reflects the amount of the response (in this case, the number of rejects) when the predictor is assumed to be 0 (in this case, the number of items produced). Thus, the model to estimate becomes

\(\begin{equation*} y_{i}=\beta_{1}x_{i}+\epsilon_{i},\end{equation*}\)

which is called a Regression Through the Origin (or RTO) model. The estimate for \(\beta_{1}\)when using the regression through the origin model is:

\(b_{\textrm{RTO}}=\dfrac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i}y_{i}}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}x_{i}^{2}}.\)

Thus, the estimated regression equation is

\(\begin{equation*} \hat{y}_{i}=b_{\textrm{RTO}}x_{i}\end{equation*}.\)

Note that we no longer have to center (or "adjust") the \(x_{i}\)'s and \(y_{i}\)'s by their sample means (compare this estimate for \(b_{1}\) to that of the estimate found for the simple linear regression model). Since there is no intercept, there is no correction factor and no adjustment for the mean (i.e., the regression line can only pivot about the point (0,0)).

Generally, regression through the origin is not recommended due to the following:

- Removal of \(\beta_{0}\) is a strong assumption that forces the line to go through the point (0,0). Imposing this restriction does not give ordinary least squares as much flexibility in finding the line of best fit for the data.

- In a simple linear regression model, \(\sum_{i=1}^{n}(y_{i}-\hat{y}_i)=\sum_{i=1}^{n}e_{i}=0\). However, in regression through the origin, generally \(\sum_{i=1}^{n}e_{i}\neq 0\). Because of this, the SSE could actually be larger than the SSTO, thus resulting in \(r^{2}<0\).

- Since \(r^{2}\) can be negative, the usual interpretation of this value as a measure of the strength of the linear component in the simple linear regression model cannot be used here.

If you strongly believe that a regression through the origin model is appropriate for your situation, then statistical testing can help justify your decision. Moreover, if data has not been collected near \(x=0\), then forcing the regression line through the origin is likely to make for a worse-fitting model. So again, this model is not usually recommended unless there is a strong belief that it is appropriate.

To fit a "regression through the origin model in Minitab click "Model" in the regular regression window and then uncheck the "Include the constant term in the model."