16 Normal Distributions

Overview

In this lesson, we’ll investigate one of the most prevalent probability distributions in the natural world, namely the normal distribution. Just as we have for other probability distributions, we’ll explore the normal distribution’s properties, as well as learn how to calculate normal probabilities.

Objectives

Upon completion of this lesson, you should be able to:

- define the probability density function of a normal random variable.

- identify the characteristics of a typical normal curve.

- transform a normal random variable \(X\) into the standard normal random variable \(Z\).

- calculate the probability that a normal random variable \(X\) falls between two values \(a\) and \(b\), below a value \(c\), or above a value \(d\).

- read standard normal probability tables.

- find the value \(x\) associated with a cumulative normal probability.

- explore the key properties, such as the moment-generating function, mean and variance, of a normal random variable.

- investigate the relationship between the standard normal random variable and a chi-square random variable with one degree of freedom.

- interpret a \(Z\)-value.

- understand why the Empirical Rule holds true.

- understand the steps involved in each of the proofs in the lesson.

- apply the methods learned in the lesson to new problems.

16.1 The Distribution and Its Characteristics

Def. 16.1 (Normal Distribution) The continuous random variable \(X\) follows a normal distribution if its probability density function is defined as:

\[ f(x)=\dfrac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \mathrm{exp}\left\{-\dfrac{1}{2} \left(\dfrac{x-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2\right\} \]

for \(-\infty<x<\infty\), \(-\infty<\mu<\infty\), and \(0<\sigma<\infty\). The mean of \(X\) is \(\mu\) and the variance of \(X\) is \(\sigma^2\). We say \(X\sim N(\mu, \sigma^2)\).

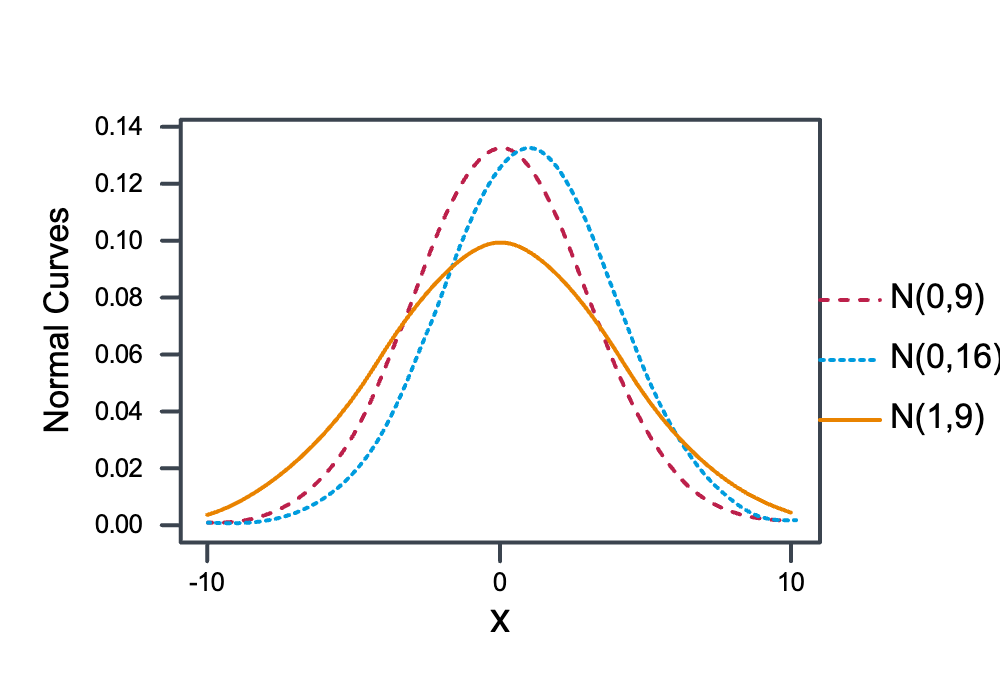

With a first exposure to the normal distribution, the probability density function in its own right is probably not particularly enlightening. Let’s take a look at an example of a normal curve, and then follow the example with a list of the characteristics of a typical normal curve.

Example 16.1 Let \(X\) denote the IQ (as determined by the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Quotient Test) of a randomly selected American. It has long been known that \(X\) follows a normal distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation of 16. That is, \(X\sim N(100, 16^2)\). Draw a picture of the normal curve, that is, the distribution, of \(X\).

Note that when drawing the above curve, I said “now what a standard normal curve looks like… it looks something like this.” It turns out that the term “standard normal curve” actually has a specific meaning in the study of probability. As we’ll soon see, it represents the case in which the mean \(\mu\) equals 0 and the standard deviation σ equals 1. So as not to cause confusion, I wish I had said “now what a typical normal curve looks like….” Anyway, on to the characteristics of all normal curves!

Characteristics of a Normal Curve

It is the following known characteristics of the normal curve that directed me in drawing the curve as I did so above.

All normal curves are bell-shaped with points of inflection at \(\mu\pm \sigma\).

All normal curves are symmetric about the mean \(\mu\).

The area under an entire normal curve is 1.

All normal curves are positive for all \(x\). That is, \(f(x)>0\) for all \(x\).

The limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) goes to infinity is 0, and the limit of \(f(x)\) as \(x\) goes to negative infinity is 0. That is:

\[ \lim\limits_{x\to \infty} f(x)=0 \text{ and } \lim\limits_{x\to -\infty} f(x)=0 \]

The height of any normal curve is maximized at \(x=\mu\).

The shape of any normal curve depends on its mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\).

16.2 Finding Normal Probabilities

Example 16.2 Let \(X\) equal the IQ of a randomly selected American. Assume \(X\sim N(100, 16^2)\).

What is the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ below 90?

Solution

As is the case with all continuous distributions, finding the probability involves finding the area under the curve and to the left of the line \(x=90\):

That is:

\[ P(X \leq 90)=F(90)=\int^{90}_{-\infty} \dfrac{1}{16\sqrt{2\pi}}\text{exp}\left\{-\dfrac{1}{2}\left(\dfrac{x-100}{16}\right)^2\right\} dx \]

There’s just one problem… it is not possible to integrate the normal PDF That is, no simple expression exists for the antiderivative. We can only approximate the integral using numerical analysis techniques. So, all we need to do is find a normal probability table for a normal distribution with mean \(\mu=100\) and standard deviation \(\sigma=16\).

Aw, geez, there’d have to be an infinite number of normal probability tables. That strategy isn’t going to work! Aha! The cumulative probabilities have been tabled for the \(N(0,1)\) distribution. All we need to do is transform our \(N(100, 16^2)\) distribution to a \(N(0, 1)\) distribution and then use the cumulative probability table for the \(N(0,1)\) distribution to calculate our desired probability. The theorem that follows tells us how to make the necessary transformation.

The theorem leads us to the following strategy for finding probabilities \(P(z<X<b)\) when \(a\) and \(b\) are constants, and \(X\) is a normal random variable with mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\):

Specify the desired probability in terms of \(X\).

Transform \(X, a\), and \(b\), by:

\[ Z=\dfrac{X-\mu}{\sigma} \]

Use the standard normal \(N(0,1)\) table, typically referred to as the \(Z\)-table, to find the desired probability.

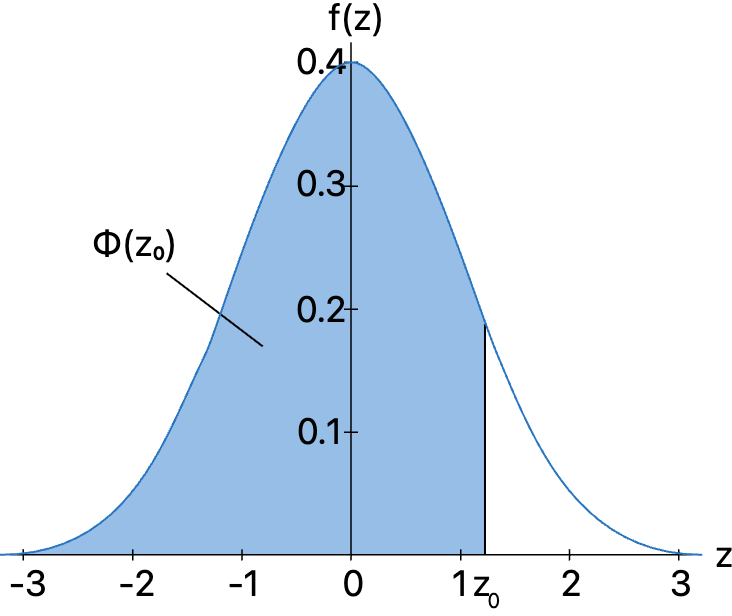

Reading \(Z\)-tables

Standard normal, or \(Z\)-tables, can take a number of different forms. There are two standard normal tables, Table Va and Table Vb, in the back of our textbook. Table Va gives the cumulative probabilities for \(Z\)-values, to two decimal places, between 0.00 and 3.09. Here’s what the top of Table Va looks like:

\[ \begin{align*} P(Z \leq z)&= \Phi(z)=\int_{-\infty}^{z} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-w^{2} / 2} dw \\ \Phi(-z) &=1-\Phi(z) \end{align*} \]

| z | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.5000 | 0.5040 | 0.5080 | 0.5120 | 0.5160 | 0.5199 | 0.5239 | 0.5279 | 0.5319 | 0.5359 |

| 0.1 | 0.5398 | 0.5438 | 0.5478 | 0.5517 | 0.5557 | 0.5596 | 0.5636 | 0.5675 | 0.5714 | 0.5753 |

| 0.2 | 0.5793 | 0.5832 | 0.5871 | 0.5910 | 0.5948 | 0.5987 | 0.6026 | 0.6064 | 0.6103 | 0.6141 |

| 0.3 | 0.6179 | 0.6217 | 0.6255 | 0.6293 | 0.6310 | 0.6368 | 0.6406 | 0.6443 | 0.6480 | 0.6517 |

| 0.4 | 0.6554 | 0.6591 | 0.6628 | 0.6664 | 0.6700 | 0.6736 | 0.6772 | 0.6808 | 0.6844 | 0.6879 |

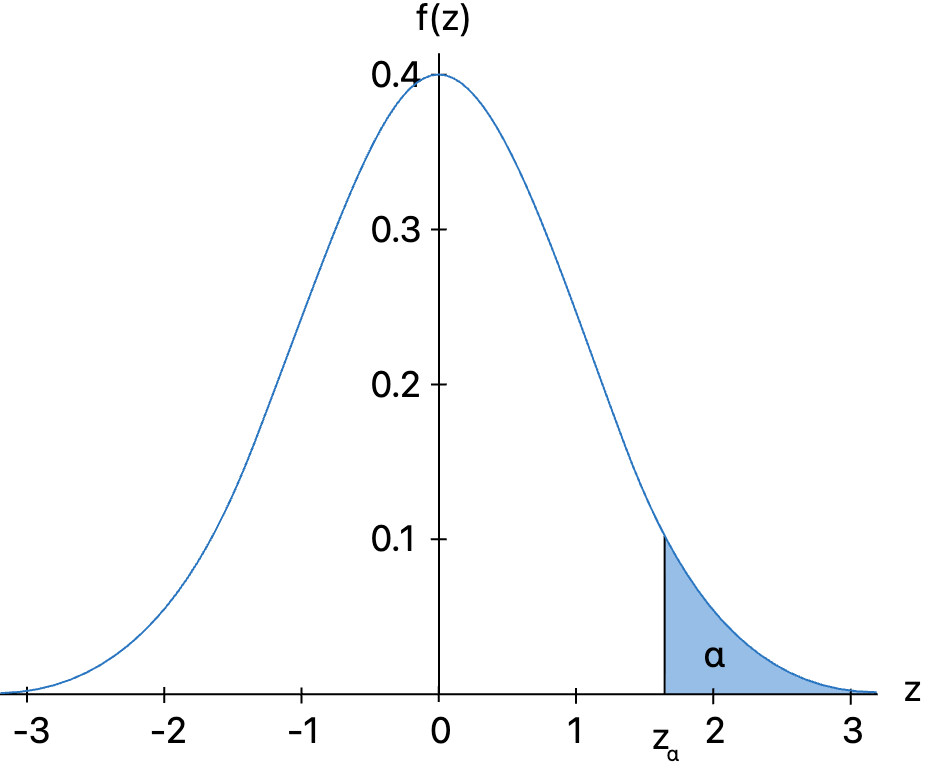

For example, you could use Table Va to find probabilities such as \(P(Z\le 0.01), P(Z\le 1.23)\), or \(P(Z\le 2.98)\). Table Vb, on the other hand, gives probabilities in the upper tail of the standard normal distribution. Here’s what the top of Table Vb looks like:

\[ P(Z > z_\alpha) = \alpha \]

\[ P(Z > z) = 1 - \Phi(z) = \Phi(-z) \]

| \(z_\alpha\) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.5000 | 0.4960 | 0.4920 | 0.4880 | 0.4840 | 0.4801 | 0.4761 | 0.4721 | 0.4681 | 0.4641 |

| 0.1 | 0.4602 | 0.4562 | 0.4522 | 0.4483 | 0.4443 | 0.4404 | 0.4364 | 0.4325 | 0.4286 | 0.4247 |

| 0.2 | 0.4207 | 0.4168 | 0.4129 | 0.4090 | 0.4520 | 0.4013 | 0.3974 | 0.3936 | 0.3897 | 0.3859 |

| 0.3 | 0.3821 | 0.3783 | 0.3745 | 0.3707 | 0.3669 | 0.3632 | 0.3594 | 0.3570 | 0.3557 | 0.3483 |

| 0.4 | 0.3446 | 0.3409 | 0.3372 | 0.3336 | 0.3300 | 0.3264 | 0.3228 | 0.3192 | 0.3192 | 0.3121 |

That is, for \(Z\)-values, to two decimal places, between 0.00 and 3.49, we can use Table Vb to find probabilities such as \(P(Z>0.12), P(Z>1.96)\), and \(P(Z>3.32)\).

Now, we just need to learn how to read the probabilities off of each of the tables. First Table Va:

And, then Table Vb:

Now we know how to read the given \(Z\)-tables. Now, we just need to work with some real examples to see that finding probabilities associated with a normal random variable usually involves rewriting the problems just a bit in order to get them to “fit” with the available \(Z\)-tables.

Example 16.3 Let \(X\) equal the IQ of a randomly selected American. Assume \(X\sim N(100, 16^2)\).

What is the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ below 90?

Solution

Whenever I am faced with finding a normal probability, I always always always draw a picture of the probability I am trying to find. Then, the problem usually just solves itself… oh, how we wish:

So, we just found that the desired probability, that is, that the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ below 90 is 0.2643. (If you haven’t already, you might want to make sure that you can independently read that probability off of Table Vb.)

Now, although I used Table Vb in finding our desired probability, it is worth mentioning that I could have alternatively used Table Va. How’s that? Well:

\[ P(X<90)=P(Z<-0.63)=P(Z>0.63)=1-P(Z<0.63) \]

where the first equality comes from the transformation from \(X\) to \(Z\), the second equality comes from the symmetry of the normal distribution, and the third equality comes from the rule of complementary events. Using Table Va to look up \(P(Z<0.63)\), we get 0.7357. Therefore,

\[ P(X<90)=1-P(Z<0.63)=1-0.7357=0.2643 \]

We should, of course, be reassured that our logic produced the same answer regardless of the method used! That’s always a good thing!

What is the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ above 140?

Solution

Again, I am going to solve this problem by drawing a picture:

So, we just found that the desired probability, that is, that the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ above 140 is 0.0062. (Again, if you haven’t already, you might want to make sure that you can independently read that probability off of Table Vb.)

We again could have alternatively used Table Va to find our desired probability:

\[ P(X>140)=P(Z>2.50)=1-P(Z<2.50 \]

where the first equality comes from the transformation from \(X\) to \(Z\), and the second equality comes from the rule of complementary events. Using Table Va to look up \(P(Z<2.5)\), we get 0.9938. Therefore,

\[ P(X>140)=1-P(Z<2.50)=1-0.9938=0.0062 \]

Again, we arrived at the same answer using two different methods.

What is the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ between 92 and 114?

Solution

Again, I am going to solve this problem by drawing a picture:

So, we just found that the desired probability, that is, that the probability that a randomly selected American has an IQ between 92 and 114 is 0.5021. (Again, if you haven’t already, you might want to make sure that you can independently read the probabilities that we used to get the answer from Tables Va and Vb.)

The previous three examples have illustrated each of the three possible normal probabilities you could be faced with finding —below some number, above some number, and between two numbers. Once you have mastered each case, then you should be able to find any normal probability when asked.

16.3 Using Normal Probabilities to Find X

On the last page, we learned how to use the standard normal curve N(0, 1) to find probabilities concerning a normal random variable X with mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\). What happens if it’s not the probability that we want to find, but rather the value of X? That’s what we’ll investigate on this page. That is, we’ll consider what I like to call “inside-out” problems, in which we use known probabilities to find the value of the normal random variable X. Let’s start with an example.

Example 16.4 Suppose X, the grade on a midterm exam, is normally distributed with mean 70 and standard deviation 10. The instructor wants to give 15% of the class an A. What cutoff should the instructor use to determine who gets an A?

Solution

My approach to solving this problem is, of course, going to involve drawing a picture:

The instructor now wants to give 10% of the class an A−.

What cutoff should the instructor use to determine who gets an A−?

Solution

We’ll use the same method as we did previously:

In summary, in order to use a normal probability to find the value of a normal random variable X:

Find the z value associated with the normal probability.

Use the transformation \(x = \mu+ z \sigma\) to find the value of x.

16.4 Normal Properties

So far, all of our attention has been focused on learning how to use the normal distribution to answer some practical problems. We’ll turn our attention for a bit to some of the theoretical properties of the normal distribution. We’ll start by verifying that the normal PDF is indeed a valid probability distribution. Then, we’ll derive the moment-generating function \(M(t)\) of a normal random variable \(X\). We’ll conclude by using the moment-generating function to prove that the mean and standard deviation of a normal random variable \(X\) are indeed, respectively, \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\), something that we thus far have assumed without proof.

The Normal PDF is Valid

Recall that the probability density function of a normal random variable is:

\[ f(x)=\dfrac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} \text{exp}\left\{-\dfrac{1}{2} \left(\dfrac{x-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2\right\} \]

for \(-\infty<x<\infty\), \(-\infty<\mu<\infty\), and \(0<\sigma<\infty\). Also recall that in order to show that the normal PDF is a valid PDF, we need to show that, firstly \(f(x)\) is always positive, and, secondly, if we integrate \(f(x)\) over the entire support, we get 1.

The Moment-Generating Function

The Mean and Variance

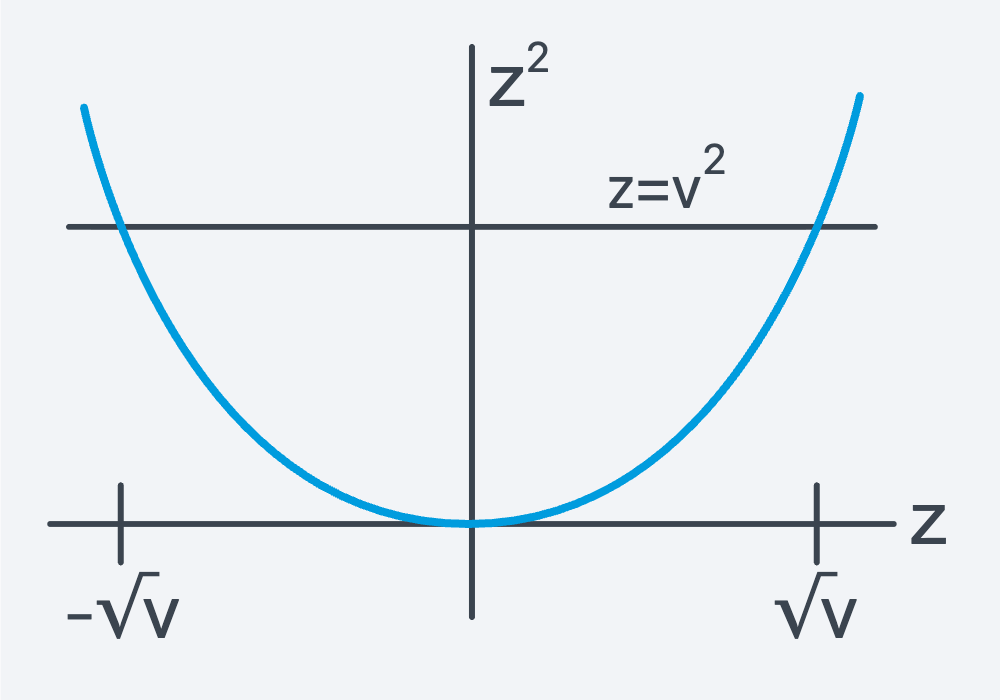

16.5 The Standard Normal and The Chi-Square

So, now that we’ve taken care of the theoretical argument. Let’s take a look at an example to see that the theorem is, in fact, believable in a practical sense.

Example 16.5 Find the probability that the standard normal random variable \(Z\) falls between −1.96 and 1.96 in two ways:

- using the standard normal distribution

- using the chi-square distribution

Solution

The standard normal table (Table V in the textbook) yields:

\[ \begin{align} P(-1.96<Z<1.96)&=P(Z<1.96)-P(Z>1.96)\\&=0.975-0.025\\&=0.95\end{align} \]

The chi-square table (Table IV in the textbook) yields the same answer:

\[ \begin{align} P(-1.96<Z<1.96)&=P(|Z|<1.96)\\&=P(Z^2<1.96^2)\\&=P(\chi^2_{(1)})<3.8416)\\&=0.95\end{align} \]

16.6 Some Applications

Interpretation of Z

Note that the transformation from \(X\) to \(Z\):

\[ Z=\dfrac{X-\mu}{\sigma} \]

tells us the number of standard deviations above or below the mean that \(X\) falls. That is, if \(Z=-2\), then we know that \(X\) falls 2 standard deviations below the mean. And if \(Z=+2\), then we know that \(X\) falls 2 standard deviations above the mean. As such, \(Z\)-scores are sometimes used in medical fields to identify whether an individual exhibits extreme values with respect to some biological or physical measurement.

Example 16.6

Post-menopausal women are known to be susceptible to severe bone loss known as osteoporosis. In some cases, bone loss can be so extreme as to cause a woman to lose a few inches of height. The spines and hips of women who are suspected of having osteoporosis are therefore routinely scanned to ensure that their bone loss hasn’t become so severe to warrant medical intervention.

The mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\) of the density of the bones in the spine, for example, are known for a healthy population. A woman is scanned and \(x\), the bone density of her spine is determined. She and her doctor would then naturally want to know whether the woman’s bone density \(x\) is extreme enough to warrant medical intervention. The most common way of evaluating whether a particular \(x\) is extreme is to use the mean \(\mu\), the standard deviation \(\sigma\), and the value \(x\) to calculate a \(Z\)-score. The \(Z\)-score can then be converted to a percentile to provide the doctor and the woman an indication of the severity of her bone loss.

Suppose the woman’s \(Z\)-score is −2.36, for example. The doctor then knows that the woman’s bone density falls 2.36 standard deviations below the average bone density of a healthy population. The doctor, furthermore, knows that fewer than 1% of the population have a bone density more extreme than that of his/her patient.

The Empirical Rule Revisited

You might recall earlier in this section, when we investigated exploring continuous data, that we learned about the Empirical Rule. Specifically, we learned that if a histogram is at least approximately bell-shaped, then:

- approximately 68% of the data fall within one standard deviation of the mean

- approximately 95% of the data fall within two standard deviations of the mean

- approximately 99.7% of the data fall within three standard deviations of the mean

Where did those numbers come from? Now, that we’ve got the normal distribution under our belt, we can see why the Empirical Rule holds true. The probability that a randomly selected data value from a normal distribution falls within one standard deviation of the mean is

\[ \begin{align} P(-1<Z<1)&=P(Z<1)-P(Z>1)\\&=0.8413-0.1587\\&=0.6826 \end{align} \]

That is, we should expect 68.26% (approximately 68%!) of the data values arising from a normal population to be within one standard deviation of the mean, that is, to fall in the interval:

\[ (\mu-\sigma, \mu+\sigma) \]

The probability that a randomly selected data value from a normal distribution falls within two standard deviations of the mean is

\[ \begin{align}P(-2<Z<2)&=P(Z<2)-P(Z>2)\\&=0.9772-0.0228\\&=0.9544\end{align} \]

That is, we should expect 95.44% (approximately 95%!) of the data values arising from a normal population to be within two standard deviations of the mean, that is, to fall in the interval:

\[ (\mu-2\sigma, \mu+2\sigma) \]

And, the probability that a randomly selected data value from a normal distribution falls within three standard deviations of the mean is:

\[ \begin{align}P(-3<Z<3)&=P(Z<3)-P(Z>3)\\&=0.9987-0.0013\\&=0.9974\end{align} \]

That is, we should expect 99.74% (almost all!) of the data values arising from a normal population to be within three standard deviations of the mean, that is, to fall in the interval:

\[ (\mu-3\sigma, \mu+3\sigma) \]

Let’s take a look at an example of the Empirical Rule in action.

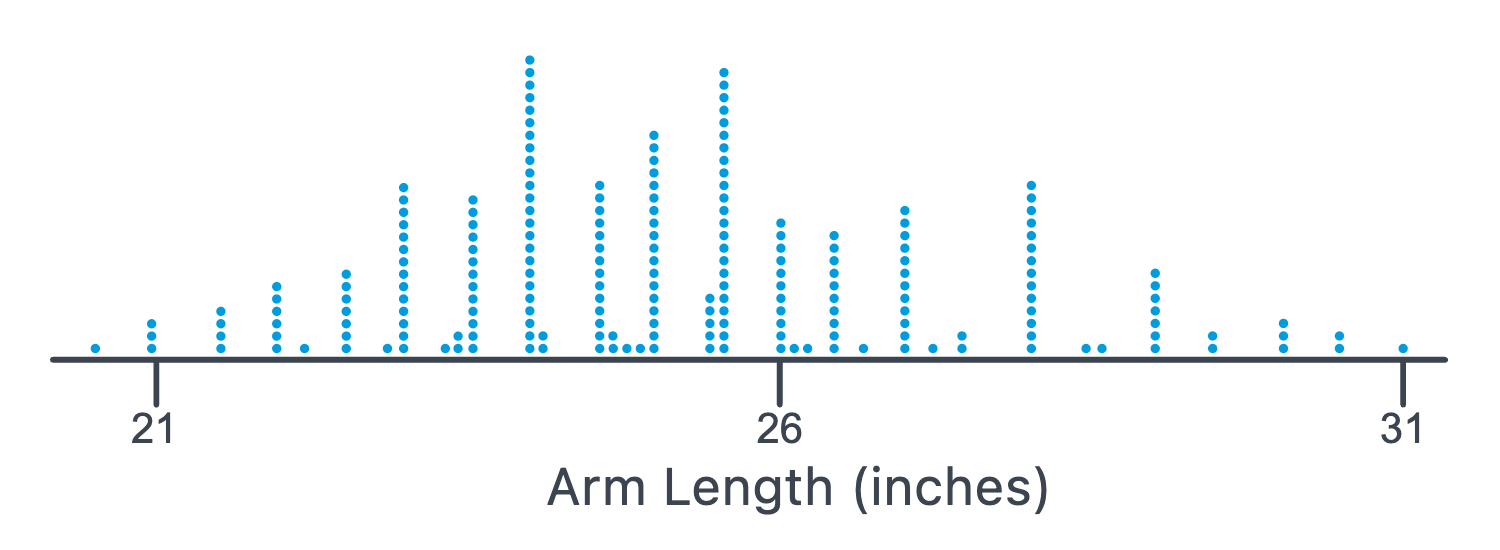

Example 16.7 The left arm length, in inches, of 213 students were measured.

Here’s the resulting data,

Show Data

…and a picture of a dot plot of the resulting arm lengths:

As you can see, the plot suggests that the distribution of the data is at least bell-shaped enough to warrant the assumption that \(X\), the left arm lengths of students, is normally distributed. We can use the raw data to determine that the average arm length of the 213 students measured is 25.167 inches, while the standard deviation is 2.095 inches. We’ll then use 25.167 as an estimate of \(\mu\), the average left arm length of all college students, and 2.095 as an estimate of \(\sigma\), the standard deviation of the left arm lengths of all college students.

The Empirical Rule tells us then that we should expect approximately 68% of all college students to have a left arm length between:

\[ \begin{align}\bar{x}-s=25.167-2.095=&23.072 \text{ and }\\ \bar{x}+s=25.167+2.095=&27.262\end{align} \]

inches. We should also expect approximately 95% of all college students to have a left arm length between:

\[ \begin{align}\bar{x}-2s=25.167-2(2.095)=&20.977 \text{ and }\\ \bar{x}+2s=25.167+2(2.095)=&29.357\end{align} \]

inches. And, we should also expect approximately 99.7% of all college students to have a left arm length between:

\[ \begin{align}\bar{x}-3s=25.167-3(2.095)=&18.882 \text{ and }\\ \bar{x}+3s=25.167+3(2.095)=&31.452\end{align} \]

Let’s see what percentage of our 213 arm lengths fall in each of these intervals! It takes some work if you try to do it by hand, but statistical software can quickly determine that:

- 143, or 67.14%, of the 213 arm lengths fall in the first interval

- 204, or 95.77%, of the 213 arm lengths fall in the second interval

- 213, or 100%, of the 213 arm lengths fall in the third interval

The Empirical Rule didn’t do too badly, eh?