For Students

For Students

Learning Online Orientation

If this is the first time that you are taking an online course, then we would strongly urge you to work through the pages that follow here. We'll go through how our online courses work, what technologies are used, proctored exams, how to be successful online, and where to go for help when you need it.

Math & Stat Reviews

Check out this section if you need a refresher on Algebra, Basic Statistical Concepts, Calculus, and more! Make sure to consult the course prerequisites to know what knowledge is expected upon entering a course.

Ethics and Statistics

At Penn State University, academic integrity is a critical ingredient in any program wether it be in residence or online. The Penn State Values were developed to embody the values that we hope our students, faculty, staff, administration, and alumni possess.

Learning Online Orientation

Learning Online OrientationWelcome to the Orientation Materials for the online courses associated with the Department of Statistics!

If this is the first time that you are taking an online course, then we would strongly urge you to work through the pages that follow here. We work hard to ensure that your learning experience is as positive for you as possible and we hope that the information and contacts that you will be introduced to in this orientation will help to point you in this direction.

Objectives

- Be able to describe the general nature of how the online courses are designed and the online course environment.

- Understand the role of students in an online course and what is expected from them.

- Be able to list a range of technologies that are used in association with our online courses and be able to assess whether the computer setup that they will be using is able to handle how materials are presented and interactions with others.

- Be able to list the various statistical software packages that are used as part of the online courses be able to describe how to obtain a copy of this software so that it can be installed before classes begin.

- Be able to list a range of resources and services that are available to Penn State students.

- Know who to contact when you need additional information about the program or about learning online at Penn State.

- Know who to contact when you need technical assistance.

Begin by reading through the pages that follow in this module. Follow the links that are presented so that you can check the various technology requirements on your own computer and make note of the different services that are described.

There will be a short quiz at the conclusion of these materials.

If you have any questions as you go through this Orientation, please feel free to contact John Haubrick, instructional designer & teaching faculty, Department of Statistics.

O.1 How do the online courses work?

O.1 How do the online courses work?The activities in the online courses offered by the Department of Statistics are found in two different but connected locations. The course administrative functions such as announcements, grade book, homework assignments, quizzes, and exams are all accessed from within Canvas, Penn State's learning management system. Here is a link to a Canvas Overview Video for Students if you want a sneak peek at how Canvas works. Other useful documentation for using Canvas can be found in the Canvas Student Guides. Lesson materials such as lecture notes, examples, animations, movie or audio clips, or other interactive pieces that are needed to help drive an important concept home are found on the companion course materials website.

Each course companion website intends to provide students with information, examples, images, formulas, or code that supplements what is presented in the required readings or in the instructor's Canvas course space. Wherever possible we try to make these interactive when this helps to aid understanding. In general, our notes strive to provide a rich narrative, liberally enhanced with graphics and augmented with video where appropriate. Where other online programs may base their online materials on recorded lectures, our approach intentionally promotes the use of short video segments that are embedded with our online materials for the purpose of presenting specific concepts, sharing worked examples, or responding to student questions. Our online material websites also include a search tool and a printer-friendly option, and all formulas and equations are rendered using MathJax (more on this later!).

FAQs

Click on the frequently asked questions below to view the answers.

An important aspect that all of the online courses include is interaction - interaction with the instructor as well as interaction among students. The course's email, discussion forums, and live chat are tools typically used for these interactions, however, many instructors take advantage of other video or interactive whiteboard types of communication tools outside of the course management system where they can work with students as a group or individually.

In Canvas you can find out who your classmates are by selecting the 'People' link on the left. Each course typically starts off with an introductory activity. Take advantage of this to introduce yourself to your instructor and your fellow classmates. Later on, in this orientation, you can follow the tips to update your profile in Canvas by clicking on your Account > Profile and adding information to this page.

Want to know more about your instructor? Start with the Online Instructors page or send them an email.

The course schedule is published along with the syllabus at the beginning of the semester by the course instructor. Depending on the course, the flexibility of the course schedule varies, but in general, our courses are pretty well packed with readings, homework, quizzes, exams, etc. We work hard to maintain the policy of Penn State University and the Department of Statistics that all of our online courses are equivalent to what would be taught in the residence course section on campus and we take this curriculum integrity issue seriously.

Our online courses all follow the same academic calendar as the rest of the university, with perhaps a few changes because it is online. And, all of our courses are cohort-based. This means that all the students start at the same time and work through the lessons at the same time, with the instructor opening and introducing perhaps a couple of lessons at a time. Our courses are not open-enrollment oriented where everyone is on their own studying at their own pace. This would make discussions problematic and the role of the instructor nearly impossible trying to direct your attention and answer questions from all directions! Also, given the wide array of time zones that our students represent, nearly all of the activities in our courses are asynchronous. Instructors may establish times for office hours that are held in an online meeting room, (recorded for those that can not attend) or an instructor may want students to present work to the class, but in general, most of the work and interaction takes place individually through email, discussion forums and other methods that do not require everyone to log in at a specified time.

The pace and approach to courses are very similar to how things are taught face-to-face. In fact, some of our online instructors are teaching the same course on campus. However, this being said, and because this is online and we realize that our online students are typically returning adult professionals with full-time work and family responsibilities, our instructors try their best to make accommodations. For instance, we've come to realize that for many the majority of the discretionary time you have to apply to coursework has been on weekends. Therefore, a Friday deadline for homework is problematic for many. We found that shifting due dates to Sunday night or Monday works better for most. Again, when something comes up, travel, medical, or other issues, that might impact your ability to meet deadlines, whenever possible reach out to your instructor ahead of time.

This is a good question, and of course, you might expect the answer, "It depends". Well, it does depend. It depends on what background understanding you bring to the course. And it depends on the course. Some may involve a lot more work for you, whereas other courses may involve much more difficult concepts or methods.

To help you answer this question, take a look at the results displayed in the pie chart (right). Every semester we administer a Mid-Semester Survey in each of our courses as a means of monitoring the perceptions of our students and providing an opportunity for feedback. These are the results combined across all of our MAS courses during the Summer 2018 semester asking how much time students spend on their course. The Graduate School guidelines at Penn State state that a student should be expected to spend 3 hours outside of class for every course credit. So, for a 3-credit course, one would expect to spend 9 hours on reading, homework, study, etc. Taking this into account, the pie chart shows us that our students are reporting that we pretty much meet this standard. For instance, 40% of students reported spending 4-6 hours on a course, and 39% of students reported spending 7-9 hours per week on a course. In the long run, we work to ensure that our courses are rigorous without being impossible and that what you learn is of lasting value.

Each course includes an assessment plan which is published as part of the course syllabus. Deadlines for each of these assignments are given in the course schedule. By the way, all of the course due date times are US Eastern Time (the Canvas timestamp) - not for each of your time zones. The deadline time is set so the grading and feedback process can begin. Keep up with the course schedule. If you get behind it is a real chore to catch up! This would be true in a face-to-face class as well.

All assessments are submitted in Canvas. Lesson quizzes are mostly multiple choice but could include T/F or essay-type questions as well. Sometimes it might be necessary to write out an assignment by hand. In these cases, students will need access to a scanner that would produce a .pdf of their work which could then be submited to your Assignment or Quiz in Canvas.

Whereas homework and labs are open until they are due, mid-terms and exams are available to be taken by students during the pre-established time frame. For instance, if a 90-minute mid-term is open beginning Thursday to Sunday, then students will need to find a 90-minute time slot somewhere in this time frame that they can complete this exam. Additionally, some courses have exams that are required to be proctored. For more information about proctored exams read What is a Proctored Exam?

Because these courses are online we will be using various technology tools. We will tackle this in the next section...

O.2 What technology is used?

O.2 What technology is used?In our online statistics courses, you will use a variety of technologies to facilitate the learning process.

The following sections highlight just a few of these technologies. Visit the Technology Tutorials on this site for more information on the technology used in our courses.

Other Resources

- Canvas Orientation

Canvas orientation course created by World Campus. - Penn State IT Connect to Tech Student Guide

Penn State's main resources for tech available to students. - Statistical Software page

Stat Department list of software needed for each course. - Technical help and support resources

List of contact information for various technical support services

Technical Requirements for Online Courses

Technical Requirements for Online CoursesRecommended Technical Requirements for "Frustration Free" Computing

View our World Campus Technical Requirements page to see the minimum technical requirements for our courses.

To review minimum technical requirements for individual statistical software packages, please visit the technical support pages of the individual vendors. See the Statistical Software page on the Statistics Department website.

Students are strongly encouraged to download, install, and test computer and browser requirements prior to the beginning of classes.

Courses with Proctored Exams

For courses using Honorlock you must meet the following technical requirements.

Honorlock System Requirements

- Desktop computer or laptop (tablets, Chromebook and cell phones do not meet our requirements)

- Windows 10 or 11

- MacOSX 10.14 and higher

- ChromeOS 93 and higher

- Webcam and microphone (built-in or external).

- Currently, Honorlock is incompatible with:

- iPads

- Walmart Branded Camera (Onn)

- Currently, Honorlock is incompatible with:

- Connection to network with sufficient internet speed: at least 1.5 Mbps download speed and 750 Sbps upload. Hot spots are not recommended.

- Chrome Browser version 93 or higher with pop-up blocker disabled

- Installed Honorlock Chrome Extension

- "Once you install the extension, you get the protection and ease of simply logging into your school’s learning management system and getting started."

- "We’ll walk you through a quick 60-second pre-test checklist to make sure you’re ready to go."

Reaching Honorlock 24/7/365 Support

- Phone: 1 (844) 243-2500

- Email: support@honorlock.com

- Live Chat: Click on the live chat link located at the bottom right corner of your Canvas exam page

- Honorlock support: Click on the link at the top right-hand corner of your Canvas exam page

Reference: July 18, 2022, Honorlock Help Center "Minimum System Requirements"

Learning Management System: Canvas

Learning Management System: CanvasThe course administrative functions such as announcements, gradebook, homework assignments, quizzes, and exams are all accessed from within Canvas, Penn State's learning management system.

There are numerous resources we recommend you review if this is your first time using Canvas.

Canvas Resources

Take a Screen Capture

Take a Screen CaptureIn the online environment, being able to capture graphs, images and equations is an important skills for assignments, discussion forums and even troubleshooting issue with your instructor to the help desk.

Most new operating systems come equipped with some sore of screen capture tool. Here are the basic ones.

Windows Windows

Using Keyboard

- PrtScn: Another option is to use the print screen ("PrtScn") function which will copy your entire screen, then paste it into Word and crop down to only the necessary part of the screen.

- SHIFT + S: (Windows 10 only)

Using built-in tool

- Snipping Tool: Computers with Windows Vista and later will have a snipping tool. This will allow you to select a portion of your screen. Then, you can copy it and paste it.

macOS macOS

Using Keyboard

- ⌘ + shift + 4: This will allow you to select a portion of your screen. By default, this saves your screenshot as a graphic

Using Built-in tool

- Grab: This tool will allow you to capture, the entire screen or just a selection.

Once you have your image you can then upload it to Canvas or add it to your document.

Uploading an image to a Canvas Forum or Quiz

As a student in our online STAT courses, you may have to upload an image to a discussion, quiz, or assignment in Canvas. Canvas provides a way to upload directly from their rich content editor.

View the step-by-step procedures in the Canvas documentation.

How do I embed images from Canvas into the rich content editor as a student?

Working with Images in Documents

Cropping a Picture in Word

There are times when you have to crop your screenshot to only show certain parts of the image in your document.

O.3 What is a proctored exam?

O.3 What is a proctored exam?Proctored Exams

Some courses require the use of Honorlock proctoring software to protect academic integrity during certain course activities. While active, this software uses your computer's webcam and microphone to record video and audio, while other technology monitors your activity, including your screen and web navigation.

You will need a computer (not a phone or tablet) with a microphone and webcam and one of the compatible operating systems listed in Honorlock's Minimum Requirements table. Additionally, you will need to use Chrome and download the Honorlock Chrome Extension.

The information collected by Honorlock is confidential and will only be used for legitimate academic and educational purposes. For further information, see the Penn State Honorlock privacy statement and Honorlock’s Student Data Privacy & Security information.

Resources:

If you have any technical issues or questions, please reach out to Honorlock support via live chat on the Honorlock support page or through the exam itself.

O.4 How can I be successful?

O.4 How can I be successful?OK, so you now have the technology all in place, your browser and plug-ins working and a reliably fast internet connection. This is good but it is just a start! There is more to learning online than just the technologies!

We want you get to most out of your online learning experience. So, we have put together a list of 'Tips & Suggestions' that have been gathered from research and our own experience working with students. We want you to listen to interviews with students who share their own advice based on their personal experiences and what they have to say about how they organize their time so that they can complete all of the necessary tasks and activities for a course.

Read through these suggestions, watch the video and then make a personal plan for an approach that will help you make the most of your online learning experience!

Tips & Suggestions

- Pay close attention to the due dates of the assignments and check the Syllabus regularly in case changes have been made by the instructor!

- Plan ahead and plan well. Do not put off quizzes or assignments till the last minute! Courses in statistics are challenging and these courses are no different. If you begin to fall behind it will be very difficult to catch up!!

- Check your e-mail regularly, but be patient while waiting for responses.

- Communicate with your instructor and/or classmates by e-mail, message boards, chat rooms, Instant Messenger, or phone. Subscribe to discussion forums so that you get notified if there is a post!

- Use courtesy in online communication and deal with conflict with respect.

- Evaluate your own progress by the course objectives and assignments, and regulate your own study pace based on this evaluation. Talk to your instructor if you encounter a problem.

- Participation is important to your learning experience in an online learning environment, so be confident in making contributions. Don't be afraid of making mistakes!

- Identify a way of taking notes you would prefer: use Word, online journal/Web logging, note-taking software, bookmarking the Web sites important to you, or any method that works well for you.

- Be aware of the resources for HELP available: your instructor, the Outreach HelpDesk, Outreach Student Services, Canvas Help, or a librarian.

- Always check the file size when you try to upload a file to share. The bigger the file size, the more difficult it may be to upload and download.

- In addition to becoming familiar with the online learning environment, pay attention to the physical learning environment around you - try to arrange everything ergonomically in your learning space.

- Be sure to always display appropriate "Netiquette". Netiquette covers not only rules to maintain civility in discussions but also special guidelines unique to the electronic nature of forum messages. View Penn State's Earth and Mineral Sciences faculty development resource on 'Netiquette'.

Ask GOOD Questions!

Communicating back and forth with your instructor and classmates using email or discussion boards can be frustrating because of the back and forth nature of trying to find out specifically what you need to know. For this reason it is important to ask questions that have enough information so to ensure that you will efficently get a helpful answer in return.

- Be Specific! For instance, if you ask, "I just don't get problem #4, can anyone help me?" - this is pretty general and I am sure potential respondents are saying, "Where do I start?!" Instead, add more specific details to help your helpers help you more efficiently. If the question posted was, "I am gettting a different value for the standard error and here are values that I am using. Can anyone see what I am doing wrong?"

- Capture Your Screen! They say a picture is worth a thousand words - so you might as well take advantage of this! Rather than explain, show what you see when you can. You can then either embed this in your message or add it as an attachment. This can save you are your instructor lots of time!

O.5 What resources are available?

O.5 What resources are available?Penn State provides a host of resources to every Penn State student. Here are some pages that we think might be of particular interest to our online students.

Penn State Information and Resources

The pages that follow provide specific information that you can skim through quickly. Perhaps something will catch your eye that you might want to investigate further.

In any course, whether it is face-to-face or online, as a student of The Pennsylvania State University, you are required and expected to understand and accept our policies on academic integrity and plagiarism. While you may have read this information in other courses, you are encouraged to re-read it.

Academic Integrity

Academic integrity is the pursuit of scholarly activity free from fraud and deception and is an educational objective of this institution. Violations of academic integrity include but are not limited to, cheating, plagiarizing, fabricating of information or citations, facilitating acts of academic dishonesty by others, having unauthorized possession of examinations, submitting work of another person or work previously used without informing the instructor or tampering with the academic work of other students. At the beginning of each course, it is the responsibility of the instructor to provide a statement clarifying the application of academic integrity criteria to that course. A student charged with academic dishonesty will be given oral or written notice of the charge by the instructor. If students believe they have been falsely accused, they should seek redress through informal discussion with the instructor, department head, dean, or campus executive officer. If the instructor believes that the infraction is sufficiently serious to warrant referral of the case to Judicial Affairs, or if the instructor will award a final grade of "F" in the course because of the infraction, the student will be afforded formal due process.

For this and every course, you are required to read and abide by Penn State's Academic Integrity Policies. Each course syllabus contains a statement similar to the one below with links to the Eberly College of Science's policies governing Academic Integrity:

All Penn State policies regarding ethics and honorable behavior apply to this course. Academic integrity is the pursuit of scholarly activity free from fraud and deception and is an educational objective of this institution. All University policies regarding academic integrity apply to this course. Academic dishonesty includes but is not limited to, cheating, plagiarizing, fabricating information or citations, facilitating acts of academic dishonesty by others, having unauthorized possession of examinations, submitting work of another person or work previously used without informing the instructor or tampering with the academic work of other students.

For any material or ideas obtained from other sources, such as the text or things you see on the web, in the library, etc., a source reference must be given. Direct quotes from any source must be identified as such.

All exam answers must be your own, and you must not provide any assistance to other students during exams. Any instances of academic dishonesty WILL be pursued under the Eberly College of Science Academic Integrity Policies concerning academic integrity.

The Eberly College of Science Code of Mutual Respect and Cooperation embodies the values that we hope our faculty, staff, and students possess and will endorse to make The Eberly College of Science a place where every individual feels respected and valued, as well as challenged and rewarded.

To learn more about specific scenarios such as: How to avoid plagiarism? Academic integrity issues that may arise when collaborating with a group? and others, visit Penn State's Academic Integrity Training. You can test your understanding of these issues and those that score 80% or better will earn a certificate.

Use the Penn State Libraries!

As a Penn State student enrolled through World Campus, you have a wealth of library resources available to you — just like on-campus students! Please review the World Campus and Distance Researchers page on the library site. Eligible users include currently enrolled or employed Penn State faculty, staff, and students in good standing who do not have access to a Penn State campus.

As a registered user of Penn State Libraries, you can...

- search for journal articles (many are even immediately available in full-text);

- request articles that aren't available in full-text and have them delivered electronically;

- borrow books and other materials and have them delivered to your doorstep;

- access materials that your instructor has put on electronic Library Reserves;

- talk to reference librarians in real time using chat, phone, and e-mail;

- ...and much more!

For additional information on using the Library as a World Campus student check out the following two flyers.

- Using the Penn State Libraries System

- How Penn State World Campus Students Can Request Library Materials

Library Contact:

Denise Wetzel

Science & Engineering Librarian

dawetzel@psu.edu

Statistics (Mathematical) Library Research Materials

Research or Subject Guides

Research guides help you find high-quality information and are created by librarians who are subject specialists in a wide array of disciplines. Search the research guides by keyword or use the alphabetical list to find the appropriate guide.

SAGE Resarch Materials

SAGE's Little Green Books, Methods Map, and Methods lists are all now available to all Penn State students for FREE! This includes the famous series, Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. This entire series is available on SAGE Research Methods, with additional tools across the site to filter your search on just these titles.

To access these SAGE Research Materials, go to the Penn State Libraries > click on the Databases tab > select 'S' > then click on the SAGE Research Methods Online link:

Penn State has been successfully offering education at a distance since 1892. One big reason for this success is because of the work of the folks in Student Services. From financial aid to technology support to career services, students are all encouraged to take advantage of the vast expertise they have gained over the years. They have recently received recognition for their work with students in the military. If you have not logged into your World Campus portal, follow the link to find out how. Penn State's World Campus has a variety of different services related to learning online that at one time or another, you may want to take advantage of.

Besides the help you may have received in getting admitted to a program, registering for courses, and technical support once your course gets started, there are also support services for students that you might not be aware of. These include:

- Financial Aid, Scholarships, and other benefits

- Support for Students in the Military

- Support for Students with Disabilities

- Career Services

Do you know how to defer loans you do have while you are a student? First, it is important to know that you have to be at least a half-time student in order to be loan eligible. And, once you have a loan it is important to demonstrate satisfactory academic performance, i.e., completing a course with a passing grade or your opportunity to obtain future aid may be in jeopardy!

World Campus provides a Student Portal that has links to help you answer all of your questions. The screenshot below of this portal points to some of the important links to check out!

Resources

There are a handful of valuable resources that every student will want to take advantage of while they are at Penn State including your account profile, Canvas, Office 365, Zoom, web publishing, software, and others. This page offers you a quick listing of services to check out!

When is the first day of classes? What does the drop/add period end? The Penn State calendars are a page that every student visits at one point or another!

O.6 Summary

O.6 SummaryThe Department of Statistics is proud to be able to offer these opportunities to learn online to individuals who otherwise might not be able to take advantage of taking a course or getting an advanced degree. We hope that the approach that we take will help you build your understanding and experience base in positive ways.

Having worked through this Orientation module you should now have a good idea as to how our online courses are delivered and the role that students play throughout the semester. Being all online you should understand that there are a number of technologies and internet resources that will be central to your success with the program. As a result, you should see the need to check the computer setup so that you have all hardware, software, and internet connection in place before any classes start. If you have any questions about any of this technical information, please do not hesitate to reach out to the contacts listed within the orientation.

Also, you should know that once you get your PSU Access Account userid, there are a host of resources available to all Penn State students, this includes through World Campus. Take advantage of these!

And, finally, if you have any questions about our courses, your program of study, or the technology, please do not hesitate to contact someone here at Penn State, in the Department of Statistics, or at one of the various Help Desks online.

Quick Tutorials

You will notice a 'Quick Tutorials' section of the website that follows this Orientation. These quick tutorials focus on some of the specific applications that are either used regularly in our online courses or tools or methods that we think will come in handy. Check them out! They are organized in terms of:

Math & Stat Reviews

Math & Stat Reviews

Algebra

Knowledge of the following mathematical operations is required for STAT 200:

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Division

- Multiplication

- Radicals (i.e., square roots)

- Exponents

- Summations \(\left( \sum \right) \)

- Factorials (!)

Basic Statistical Concepts

These review materials are intended to provide a review of key statistical concepts and procedures. Specifically, the lesson reviews:

- populations and parameters and how they differ from samples and statistics,

- confidence intervals and their interpretation,

- hypothesis testing procedures, including the critical value approach and the P-value approach,

- chi-square analysis,

- tests of proportion, and

- power analysis.

Calculus

It is imperative that you have a working knowledge of multidimensional calculus as a prerequisite.

This includes:

- differentiation,

- integration,

- series,

- limits, and

- multivariate calculus.

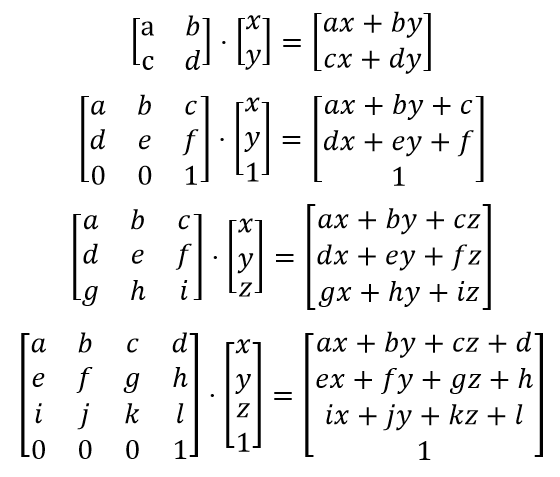

Matrix Algebra

Students who do not have this foundation or have not reviewed this material within the past couple of years will struggle with the concepts and methods that build on this foundation.

Algebra Review

Algebra ReviewKnowledge of the following mathematical operations is required for STAT 200:

- Addition

- Subtraction

- Division

- Multiplication

- Radicals (i.e., square roots)

- Exponents

- Summations \(\left( \sum \right) \)

- Factorials (!)

Additionally, the ability to perform these operations in the appropriate order is necessary. Use these materials to check your understanding and preparation for taking STAT 200.

We want our students to be successful! And we know that students that do not possess a working knowledge of these topics will struggle to participate successfully in STAT 200.

Review Materials

Are you ready? As a means of helping students assess whether or not what they currently know and can do meets the expectations of instructors of STAT 200, the online program has put together a brief review of these concepts and methods. This is then followed by a short self-assessment exam that will help you determine if this prerequisite knowledge is readily available for you to apply.

Self-Assessment Procedure

- Review the concepts and methods on the pages in this section of this website.

- Download and complete the Self-Assessment Exam.

- Review the Self-Assessment Exam Solutions and determine your score.

Your score on this self-assessment should be 100%! If your score is below this you should consider further review of these materials and are strongly encouraged to take MATH 021 or an equivalent course.

If you have struggled with the methods that are presented in the self-assessment, you will indeed struggle in the courses that expect this foundation.

Note: These materials are NOT intended to be a complete treatment of the ideas and methods used in algebra. These materials and the self-assessment are simply intended as simply an 'early warning signal' for students. Also, please note that completing the self-assessment successfully does not automatically ensure success in any of the courses that use these foundation materials. Please keep in mind that this is a review only. It is not an exhaustive list of the material you need to have learned in your previous math classes. This review is meant only to be a simple guide of things you should remember and that we build upon in STAT 200.

A.1 Order of Operations

A.1 Order of OperationsWhen performing a series of mathematical operations, begin with those inside parentheses or brackets. Next, calculate any exponents or square roots. This is followed by multiplication and division, and finally, addition and subtraction.

- Parentheses

- Exponents & Square Roots

- Multiplication and Division

- Addition and Subtraction

Example A.1

Simplify: $(5+\dfrac{9}{3})^{2}$

\end{align}

Example A.2

Simplify: $\dfrac{5+6+7}{3}$

\end{align}

Example A.3

Simplify: $\dfrac{2^{2}+3^{2}+4^{2}}{3-1}$

A.2 Summations

A.2 SummationsThis is the upper-case Greek letter sigma. A sigma tells us that we need to sum (i.e., add) a series of numbers.

\[\sum\]

For example, four children are comparing how many pieces of candy they have:

| ID | Child | Pieces of Candy |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marty | 9 |

| 2 | Harold | 8 |

| 3 | Eugenia | 10 |

| 4 | Kevi | 8 |

We could say that: \(x_{1}=9\), \(x_{2}=8\), \(x_{3}=10\), and \(x_{4}=8\).

If we wanted to know how many total pieces of candy the group of children had, we could add the four numbers. The notation for this is:

\[\sum x_{i}\]

So, for this example, \(\sum x_{i}=9+8+10+8=35\)

To conclude, combined, the four children have 35 pieces of candy.

In statistics, some equations include the sum of all of the squared values (i.e., square each item, then add). The notation is:

\[\sum x_{i}^{2}\]

or

\[\sum (x_{i}^{2})\]

Here, \(\sum x_{i}^{2}=9^{2}+8^{2}+10^{2}+8^{2}=81+64+100+64=309\).

Sometimes we want to square a series of numbers that have already been added. The notation for this is:

\[(\sum x_{i})^{2}\]

Here,\( (\sum x_{i})^{2}=(9+8+10+8)^{2}=35^{2}=1225\)

Note that \(\sum x_{i}^{2}\) and \((\sum x_{i})^{2}\) are different.

Summations

Here is a brief review of summations as they will be applied in STAT 200:

A.3 Factorials

A.3 FactorialsFactorials are symbolized by exclamation points (!).

A factorial is a mathematical operation in which you multiply the given number by all of the positive whole numbers less than it. In other words \(n!=n \times (n-1) \times … \times 2 \times 1\).

For example,

“Four factorial” = \(4!=4\times3\times2\times1=24\)

“Six factorial” = \(6!=6\times5\times4\times3\times2\times1)=720\)

When we discuss probability distributions in STAT 200 we will see a formula that involves dividing factorials. For example,

\[\frac{3!}{2!}=\frac{3\times2\times1}{2\times1}=3\]

Here is another example,

\[\frac{6!}{2!(6-2)!}=\frac{6\times5\times4\times3\times2\times1}{(2\times1)(4\times3\times2\times1)}=\frac{6\times5}{2}=\frac{30}{2}=15\]

Also, note that 0! = 1

Factorials

Here is a brief review of factorials as they will be applied in STAT 200:

A.4 Self-Assess

A.4 Self-AssessSelf-Assessment Procedure

- Review the concepts and methods on the pages in this section of this website.

- Download and Complete the STAT 200 Algebra Self-Assessment

- Determine your Score by Reviewing the STAT 200 Algebra Self-Assessment: Solutions.

Your score on this self-assessment should be 100%! If your score is below this you should consider further review of these materials and are strongly encouraged to take MATH 021 or an equivalent course.

If you have struggled with the methods that are presented in the self assessment, you will indeed struggle in the courses above that expect this foundation.

Note: These materials are NOT intended to be a complete treatment of the ideas and methods used in these algebra methods. These materials and the accompanying self-assessment are simply intended as simply an 'early warning signal' for students. Also, please note that completing the self-assessment successfully does not automatically ensure success in any of the courses that use this foundation.

Basic Statistical Concepts

Basic Statistical ConceptsThe Prerequisites Checklist page on the Department of Statistics website lists a number of courses that require a foundation of basic statistical concepts as a prerequisite. All of the graduate courses in the Master of Applied Statistics program heavily rely on these concepts and procedures. Therefore, it is imperative — after you study and work through this lesson — that you thoroughly understand all the material presented here. Students that do not possess a firm understanding of these basic concepts will struggle to participate successfully in any of the graduate-level courses above STAT 500. Courses such as STAT 501 - Regression Methods or STAT 502 - Analysis of Variance and Design of Experiments require and build from this foundation.

Review Materials

These review materials are intended to provide a review of key statistical concepts and procedures. Specifically, the lesson reviews:

- populations and parameters and how they differ from samples and statistics,

- confidence intervals and their interpretation,

- hypothesis testing procedures, including the critical value approach and the P-value approach,

- chi-square analysis,

- tests of proportion, and

- power analysis.

For instance, with regards to hypothesis testing, some of you may have learned only one approach — some the P-value approach, and some the critical value approach. It is important that you understand both approaches. If the P-value approach is new to you, you might have to spend a little more time on this lesson than if not.

Learning Objectives & Outcomes

Upon completion of this review of basic statistical concepts, you should be able to do the following:

-

Distinguish between a population and a sample.

-

Distinguish between a parameter and a statistic.

-

Understand the basic concept and the interpretation of a confidence interval.

-

Know the general form of most confidence intervals.

-

Be able to calculate a confidence interval for a population mean µ.

-

Understand how different factors affect the length of the t-interval for the population mean µ.

-

Understand the general idea of hypothesis testing -- especially how the basic procedure is similar to that followed for criminal trials conducted in the United States.

-

Be able to distinguish between the two types of errors that can occur whenever a hypothesis test is conducted.

-

Understand the basic procedures for the critical value approach to hypothesis testing. Specifically, be able to conduct a hypothesis test for the population mean µ using the critical value approach.

-

Understand the basic procedures for the P-value approach to hypothesis testing. Specifically, be able to conduct a hypothesis test for the population mean µ using the P-value approach.

- Understand the basic procedures for testing the independence of two categorical variables using a Chi-square test of independence.

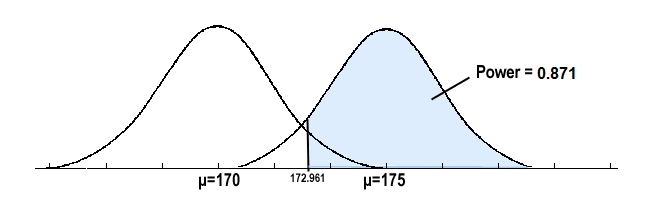

- Be able to determine if a test contains enough power to make a reasonable conclusion using power analysis.

- Be able to use power analysis to calculate the number of samples required to achieve a specified level of power.

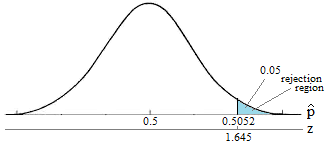

- Understand how a test of proportion can be used to assess whether a sample from a population represents the true proportion of the entire population.

Self-Assessment Procedure

- Review the concepts and methods on the pages in this section of this website.

- Download and complete the Self-Assessment Exam at the end of this section.

- Review the Self-Assessment Exam Solutions and determine your score.

A score below 70% suggests that the concepts and procedures that are covered in STAT 500 have not been mastered adequately. Students are strongly encouraged to take STAT 500, thoroughly review the materials that are covered in the sections above or take additional coursework that focuses on these foundations.

If you have struggled with the concepts and methods that are presented here, you will indeed struggle in any of the graduate-level courses included in the Master of Applied Statistics program above STAT 500 that expect and build on this foundation.

S.1 Basic Terminology

S.1 Basic TerminologyPopulation and Parameters

- Population

- A population is any large collection of objects or individuals, such as Americans, students, or trees about which information is desired.

- Parameter

- A parameter is any summary number, like an average or percentage, that describes the entire population.

The population mean \(\mu\) (the greek letter "mu") and the population proportion p are two different population parameters. For example:

- We might be interested in learning about \(\mu\), the average weight of all middle-aged female Americans. The population consists of all middle-aged female Americans, and the parameter is µ.

- Or, we might be interested in learning about p, the proportion of likely American voters approving of the president's job performance. The population comprises all likely American voters, and the parameter is p.

The problem is that 99.999999999999... % of the time, we don't — or can't — know the real value of a population parameter. The best we can do is estimate the parameter! This is where samples and statistics come in to play.

Samples and statistics

- Sample

- A sample is a representative group drawn from the population.

- Statistic

- A statistic is any summary number, like an average or percentage, that describes the sample.

The sample mean, \(\bar{x}\), and the sample proportion \(\hat{p}\) are two different sample statistics. For example:

- We might use \(\bar{x}\), the average weight of a random sample of 100 middle-aged female Americans, to estimate µ, the average weight of all middle-aged female Americans.

- Or, we might use \(\hat{p}\), the proportion in a random sample of 1000 likely American voters who approve of the president's job performance, to estimate p, the proportion of all likely American voters who approve of the president's job performance.

Because samples are manageable in size, we can determine the actual value of any statistic. We use the known value of the sample statistic to learn about the unknown value of the population parameter.

Example S.1.1

What was the prevalence of smoking at Penn State University before the 'no smoking' policy?

The main campus at Penn State University has a population of approximately 42,000 students. A research question is "What proportion of these students smoke regularly?" A survey was administered to a sample of 987 Penn State students. Forty-three percent (43%) of the sampled students reported that they smoked regularly. How confident can we be that 43% is close to the actual proportion of all Penn State students who smoke?

- The population is all 42,000 students at Penn State University.

- The parameter of interest is p, the proportion of students at Penn State University who smoke regularly.

- The sample is a random selection of 987 students at Penn State University.

- The statistic is the proportion, \(\hat{p}\), of the sample of 987 students who smoke regularly. The value of the sample proportion is 0.43.

Example S.1.2

Are the grades of college students inflated?

Let's suppose that there exists a population of 7 million college students in the United States today. (The actual number depends on how you define "college student.") And, let's assume that the average GPA of all of these college students is 2.7 (on a 4-point scale). If we take a random sample of 100 college students, how likely is it that the sampled 100 students would have an average GPA as large as 2.9 if the population average was 2.7?

- The population is equal to all 7 million college students in the United States today.

- The parameter of interest is µ, the average GPA of all college students in the United States today.

- The sample is a random selection of 100 college students in the United States.

- The statistic is the mean grade point average, \(\bar{x}\), of the sample of 100 college students. The value of the sample mean is 2.9.

Example S.1.3

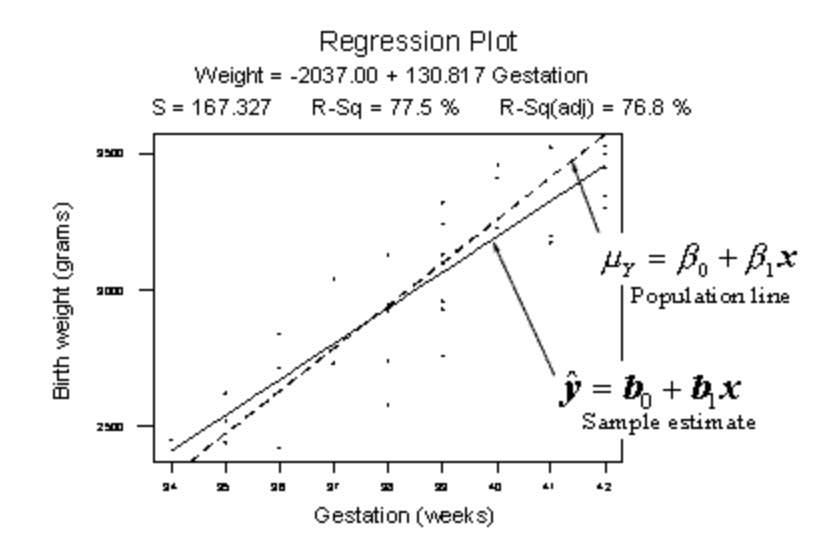

Is there a linear relationship between birth weight and length of gestation?

Consider the relationship between the birth weight of a baby and the length of its gestation:

The dashed line summarizes the (unknown) relationship —\(\mu_Y = \beta_0+\beta_1x\)— between birth weight and gestation length of all births in the population. The solid line summarizes the relationship —\(\hat{y} = \beta_0+\beta_1x\)— between birth weight and gestation length in our random sample of 32 births. The goal of linear regression analysis is to use the solid line (the sample) in hopes of learning about the dashed line (the population).

Next... Confidence intervals and hypothesis tests

There are two ways to learn about a population parameter.

1) We can use confidence intervals to estimate parameters.

"We can be 95% confident that the proportion of Penn State students who have a tattoo is between 5.1% and 15.3%."

2) We can use hypothesis tests to test and ultimately draw conclusions about the value of a parameter.

"There is enough statistical evidence to conclude that the mean normal body temperature of adults is lower than 98.6 degrees F."

We review these two methods in the next two sections.

S.2 Confidence Intervals

S.2 Confidence IntervalsLet's review the basic concept of a confidence interval.

Suppose we want to estimate an actual population mean \(\mu\). As you know, we can only obtain \(\bar{x}\), the mean of a sample randomly selected from the population of interest. We can use \(\bar{x}\) to find a range of values:

\[\text{Lower value} < \text{population mean}\;\; \mu < \text{Upper value}\]

that we can be really confident contains the population mean \(\mu\). The range of values is called a "confidence interval."

Example S.2.1

Should using a hand-held cell phone while driving be illegal?

There is little doubt that you have seen numerous confidence intervals for population proportions reported in newspapers over the years.

For example, a newspaper report (ABC News poll, May 16-20, 2001) was concerned about whether or not U.S. adults thought using a hand-held cell phone while driving should be illegal. Of the 1,027 U.S. adults randomly selected for participation in the poll, 69% believed it should be illegal. The reporter claimed that the poll's "margin of error" was 3%. Therefore, the confidence interval for the (unknown) population proportion p is 69% ± 3%. That is, we can be really confident that between 66% and 72% of all U.S. adults think using a hand-held cell phone while driving a car should be illegal.

General Form of (Most) Confidence Intervals

The previous example illustrates the general form of most confidence intervals, namely:

$\text{Sample estimate} \pm \text{margin of error}$

The lower limit is obtained by:

$\text{the lower limit L of the interval} = \text{estimate} - \text{margin of error}$

The upper limit is obtained by:

$\text{the upper limit U of the interval} = \text{estimate} + \text{margin of error}$

Once we've obtained the interval, we can claim that we are really confident that the value of the population parameter is somewhere between the value of L and the value of U.

So far, we've been very general in our discussion of the calculation and interpretation of confidence intervals. To be more specific about their use, let's consider a specific interval, namely the "t-interval for a population mean µ."

(1-α)100% t-interval for the population mean \(\mu\)

If we are interested in estimating a population mean \(\mu\), it is very likely that we would use the t-interval for a population mean \(\mu\).

- t-Interval for a Population Mean

- The formula for the confidence interval in words is:

$\text{Sample mean} \pm (\text{t-multiplier} \times \text{standard error})$

- and you might recall that the formula for the confidence interval in notation is:

- $\bar{x}\pm t_{\alpha/2, n-1}\left(\dfrac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\right)$

Note that:

- the "t-multiplier," which we denote as \(t_{\alpha/2, n-1}\), depends on the sample size through n - 1 (called the "degrees of freedom") and the confidence level \((1-\alpha)\times100%\) through \(\frac{\alpha}{2}\).

- the "standard error," which is \(\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\), quantifies how much the sample means \(\bar{x}\) vary from sample to sample. That is, the standard error is just another name for the estimated standard deviation of all the possible sample means.

- the quantity to the right of the ± sign, i.e., "t-multiplier × standard error," is just a more specific form of the margin of error. That is, the margin of error in estimating a population mean µ is calculated by multiplying the t-multiplier by the standard error of the sample mean.

- the formula is only appropriate if a certain assumption is met, namely that the data are normally distributed.

Clearly, the sample mean \(\bar{x}\), the sample standard deviation s, and the sample size n are all readily obtained from the sample data. Now, we need to review how to obtain the value of the t-multiplier, and we'll be all set.

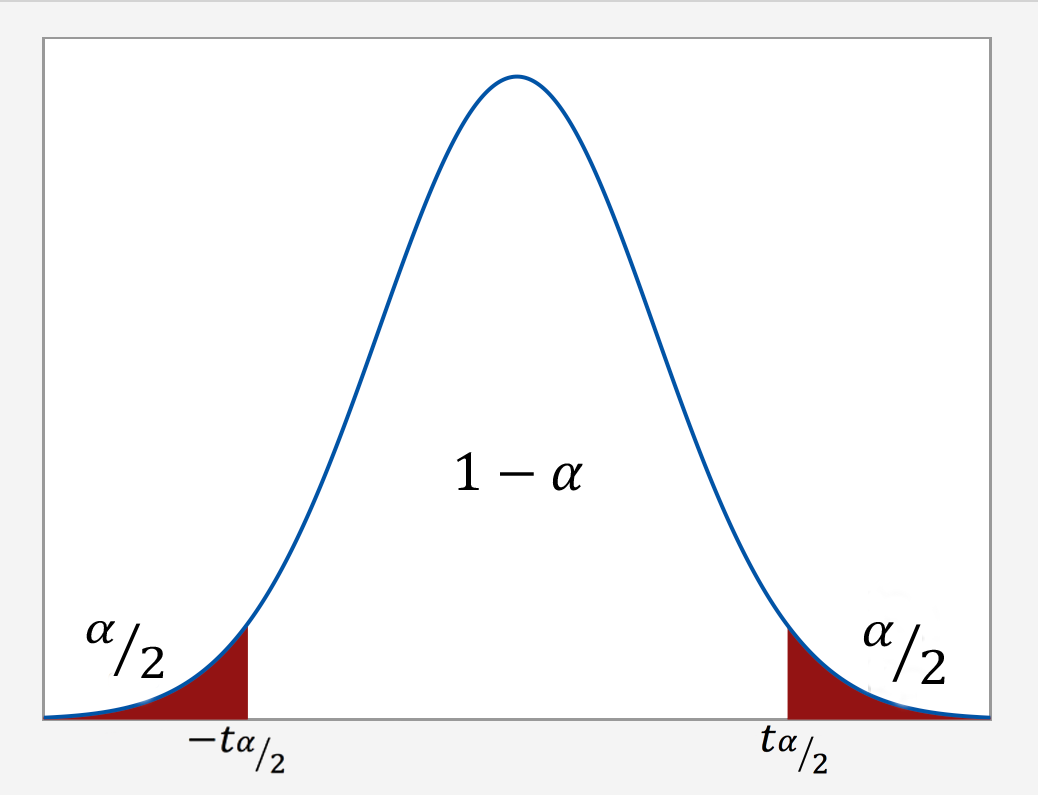

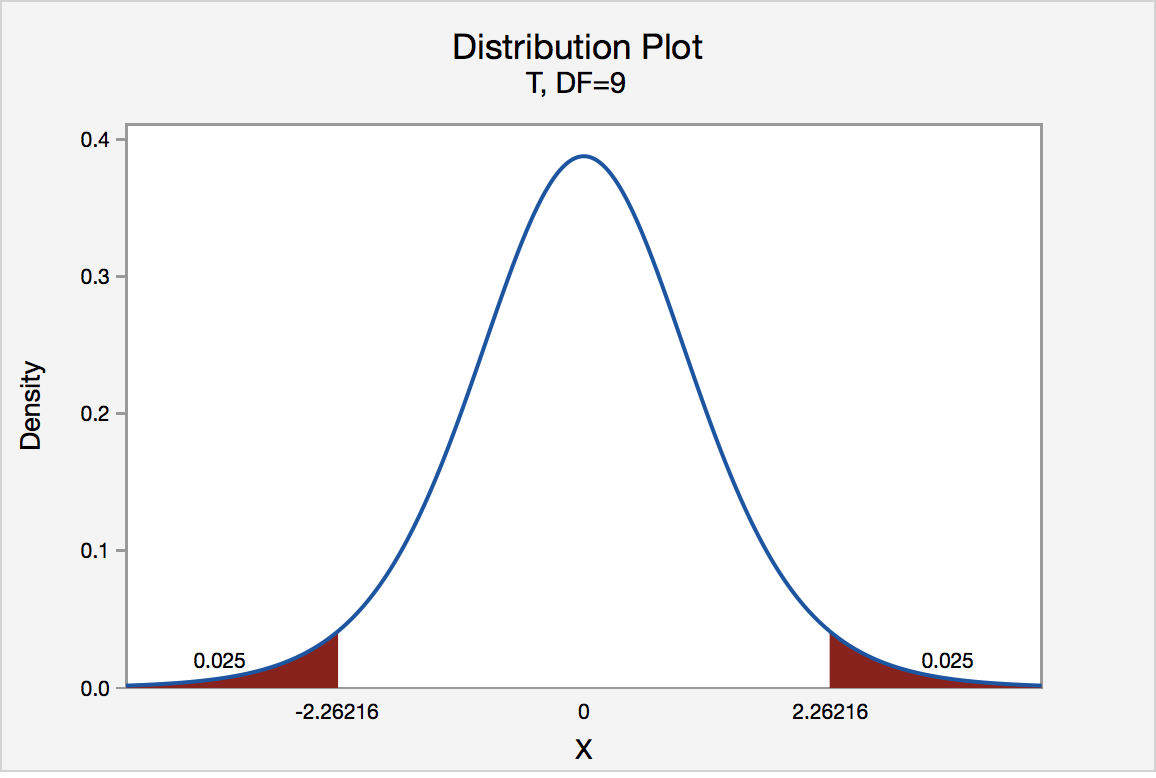

How is the t-multiplier determined?

As the following graph illustrates, we put the confidence level $1-\alpha$ in the center of the t-distribution. Then, since the entire probability represented by the curve must equal 1, a probability of α must be shared equally among the two "tails" of the distribution. That is, the probability of the left tail is $\frac{\alpha}{2}$ and the probability of the right tail is $\frac{\alpha}{2}$. If we add up the probabilities of the various parts $(\frac{\alpha}{2} + 1-\alpha + \frac{\alpha}{2})$, we get 1. The t-multiplier, denoted \(t_{\alpha/2}\), is the t-value such that the probability "to the right of it" is $\frac{\alpha}{2}$:

It should be no surprise that we want to be as confident as possible when we estimate a population parameter. This is why confidence levels are typically very high. The most common confidence levels are 90%, 95%, and 99%. The following table contains a summary of the values of \(\frac{\alpha}{2}\) corresponding to these common confidence levels. (Note that the"confidence coefficient" is merely the confidence level reported as a proportion rather than as a percentage.)

| Confidence Coefficient $(1-\alpha)$ | Confidence Level $(1-\alpha) \times 100$ | $(1-\dfrac{\alpha}{2})$ | $\dfrac{\alpha}{2}$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.90 | 90% | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| 0.95 | 95% | 0.975 | 0.025 |

| 0.99 | 99% | 0.995 | 0.005 |

Minitab® – Using Software

The good news is that statistical software, such as Minitab, will calculate most confidence intervals for us.

Let's take an example of researchers who are interested in the average heart rate of male college students. Assume a random sample of 130 male college students were taken for the study.

The following is the Minitab Output of a one-sample t-interval output using this data.

One-Sample T: Heart Rate

Descriptive Statistics

| N | Mean | StDev | SE Mean | 95% CI for $\mu$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 130 | 73.762 | 7.062 | 0.619 | (72.536, 74.987) |

$\mu$: mean of HR

In this example, the researchers were interested in estimating \(\mu\), the heart rate. The output indicates that the mean for the sample of n = 130 male students equals 73.762. The sample standard deviation (StDev) is 7.062 and the estimated standard error of the mean (SE Mean) is 0.619. The 95% confidence interval for the population mean $\mu$ is (72.536, 74.987). We can be 95% confident that the mean heart rate of all male college students is between 72.536 and 74.987 beats per minute.

Factors Affecting the Width of the t-interval for the Mean $\mu$

Think about the width of the interval in the previous example. In general, do you think we desire narrow confidence intervals or wide confidence intervals? If you are not sure, consider the following two intervals:

- We are 95% confident that the average GPA of all college students is between 1.0 and 4.0.

- We are 95% confident that the average GPA of all college students is between 2.7 and 2.9.

Which of these two intervals is more informative? Of course, the narrower one gives us a better idea of the magnitude of the true unknown average GPA. In general, the narrower the confidence interval, the more information we have about the value of the population parameter. Therefore, we want all of our confidence intervals to be as narrow as possible. So, let's investigate what factors affect the width of the t-interval for the mean \(\mu\).

Of course, to find the width of the confidence interval, we just take the difference in the two limits:

Width = Upper Limit - Lower Limit

What factors affect the width of the confidence interval? We can examine this question by using the formula for the confidence interval and seeing what would happen should one of the elements of the formula be allowed to vary.

\[\bar{x}\pm t_{\alpha/2, n-1}\left(\dfrac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\right)\]

What is the width of the t-interval for the mean? If you subtract the lower limit from the upper limit, you get:

\[\text{Width }=2 \times t_{\alpha/2, n-1}\left(\dfrac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\right)\]

Now, let's investigate the factors that affect the length of this interval. Convince yourself that each of the following statements is accurate:

- As the sample mean increases, the length stays the same. That is, the sample mean plays no role in the width of the interval.

- As the sample standard deviation s decreases, the width of the interval decreases. Since s is an estimate of how much the data vary naturally, we have little control over s other than making sure that we make our measurements as carefully as possible.

- As we decrease the confidence level, the t-multiplier decreases, and hence the width of the interval decreases. In practice, we wouldn't want to set the confidence level below 90%.

- As we increase the sample size, the width of the interval decreases. This is the factor that we have the most flexibility in changing, the only limitation being our time and financial constraints.

In Closing

In our review of confidence intervals, we have focused on just one confidence interval. The important thing to recognize is that the topics discussed here — the general form of intervals, determination of t-multipliers, and factors affecting the width of an interval — generally extend to all of the confidence intervals we will encounter in this course.

S.3 Hypothesis Testing

S.3 Hypothesis TestingIn reviewing hypothesis tests, we start first with the general idea. Then, we keep returning to the basic procedures of hypothesis testing, each time adding a little more detail.

The general idea of hypothesis testing involves:

- Making an initial assumption.

- Collecting evidence (data).

- Based on the available evidence (data), deciding whether to reject or not reject the initial assumption.

Every hypothesis test — regardless of the population parameter involved — requires the above three steps.

Example S.3.1

Is Normal Body Temperature Really 98.6 Degrees F?

Consider the population of many, many adults. A researcher hypothesized that the average adult body temperature is lower than the often-advertised 98.6 degrees F. That is, the researcher wants an answer to the question: "Is the average adult body temperature 98.6 degrees? Or is it lower?" To answer his research question, the researcher starts by assuming that the average adult body temperature was 98.6 degrees F.

Then, the researcher went out and tried to find evidence that refutes his initial assumption. In doing so, he selects a random sample of 130 adults. The average body temperature of the 130 sampled adults is 98.25 degrees.

Then, the researcher uses the data he collected to make a decision about his initial assumption. It is either likely or unlikely that the researcher would collect the evidence he did given his initial assumption that the average adult body temperature is 98.6 degrees:

- If it is likely, then the researcher does not reject his initial assumption that the average adult body temperature is 98.6 degrees. There is not enough evidence to do otherwise.

- If it is unlikely, then:

- either the researcher's initial assumption is correct and he experienced a very unusual event;

- or the researcher's initial assumption is incorrect.

In statistics, we generally don't make claims that require us to believe that a very unusual event happened. That is, in the practice of statistics, if the evidence (data) we collected is unlikely in light of the initial assumption, then we reject our initial assumption.

Example S.3.2

Criminal Trial Analogy

One place where you can consistently see the general idea of hypothesis testing in action is in criminal trials held in the United States. Our criminal justice system assumes "the defendant is innocent until proven guilty." That is, our initial assumption is that the defendant is innocent.

In the practice of statistics, we make our initial assumption when we state our two competing hypotheses -- the null hypothesis (H0) and the alternative hypothesis (HA). Here, our hypotheses are:

- H0: Defendant is not guilty (innocent)

- HA: Defendant is guilty

In statistics, we always assume the null hypothesis is true. That is, the null hypothesis is always our initial assumption.

The prosecution team then collects evidence — such as finger prints, blood spots, hair samples, carpet fibers, shoe prints, ransom notes, and handwriting samples — with the hopes of finding "sufficient evidence" to make the assumption of innocence refutable.

In statistics, the data are the evidence.

The jury then makes a decision based on the available evidence:

- If the jury finds sufficient evidence — beyond a reasonable doubt — to make the assumption of innocence refutable, the jury rejects the null hypothesis and deems the defendant guilty. We behave as if the defendant is guilty.

- If there is insufficient evidence, then the jury does not reject the null hypothesis. We behave as if the defendant is innocent.

In statistics, we always make one of two decisions. We either "reject the null hypothesis" or we "fail to reject the null hypothesis."

Errors in Hypothesis Testing

Did you notice the use of the phrase "behave as if" in the previous discussion? We "behave as if" the defendant is guilty; we do not "prove" that the defendant is guilty. And, we "behave as if" the defendant is innocent; we do not "prove" that the defendant is innocent.

This is a very important distinction! We make our decision based on evidence not on 100% guaranteed proof. Again:

- If we reject the null hypothesis, we do not prove that the alternative hypothesis is true.

- If we do not reject the null hypothesis, we do not prove that the null hypothesis is true.

We merely state that there is enough evidence to behave one way or the other. This is always true in statistics! Because of this, whatever the decision, there is always a chance that we made an error.

Let's review the two types of errors that can be made in criminal trials:

| Jury Decision | Truth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Guilty | Guilty | ||

| Not Guilty | OK | ERROR | |

| Guilty | ERROR | OK | |

Table S.3.2 shows how this corresponds to the two types of errors in hypothesis testing.

| Decision | Truth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis | Alternative Hypothesis | ||

| Do not Reject Null | OK | Type II Error | |

| Reject Null | Type I Error | OK | |

Note that, in statistics, we call the two types of errors by two different names -- one is called a "Type I error," and the other is called a "Type II error." Here are the formal definitions of the two types of errors:

- Type I Error

- The null hypothesis is rejected when it is true.

- Type II Error

- The null hypothesis is not rejected when it is false.

There is always a chance of making one of these errors. But, a good scientific study will minimize the chance of doing so!

Making the Decision

Recall that it is either likely or unlikely that we would observe the evidence we did given our initial assumption. If it is likely, we do not reject the null hypothesis. If it is unlikely, then we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. Effectively, then, making the decision reduces to determining "likely" or "unlikely."

In statistics, there are two ways to determine whether the evidence is likely or unlikely given the initial assumption:

- We could take the "critical value approach" (favored in many of the older textbooks).

- Or, we could take the "P-value approach" (what is used most often in research, journal articles, and statistical software).

In the next two sections, we review the procedures behind each of these two approaches. To make our review concrete, let's imagine that μ is the average grade point average of all American students who major in mathematics. We first review the critical value approach for conducting each of the following three hypothesis tests about the population mean $\mu$:

|

Type

|

Null

|

Alternative

|

|---|---|---|

|

Right-tailed

|

H0 : μ = 3

|

HA : μ > 3

|

|

Left-tailed

|

H0 : μ = 3

|

HA : μ < 3

|

|

Two-tailed

|

H0 : μ = 3

|

HA : μ ≠ 3

|

In Practice

-

We would want to conduct the first hypothesis test if we were interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group is more than 3.

-

We would want to conduct the second hypothesis test if we were interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group is less than 3.

-

And, we would want to conduct the third hypothesis test if we were only interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group differs from 3 (without caring whether it is more or less than 3).

Upon completing the review of the critical value approach, we review the P-value approach for conducting each of the above three hypothesis tests about the population mean \(\mu\). The procedures that we review here for both approaches easily extend to hypothesis tests about any other population parameter.

S.3.1 Hypothesis Testing (Critical Value Approach)

S.3.1 Hypothesis Testing (Critical Value Approach)The critical value approach involves determining "likely" or "unlikely" by determining whether or not the observed test statistic is more extreme than would be expected if the null hypothesis were true. That is, it entails comparing the observed test statistic to some cutoff value, called the "critical value." If the test statistic is more extreme than the critical value, then the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis. If the test statistic is not as extreme as the critical value, then the null hypothesis is not rejected.

Specifically, the four steps involved in using the critical value approach to conducting any hypothesis test are:

- Specify the null and alternative hypotheses.

- Using the sample data and assuming the null hypothesis is true, calculate the value of the test statistic. To conduct the hypothesis test for the population mean μ, we use the t-statistic \(t^*=\frac{\bar{x}-\mu}{s/\sqrt{n}}\) which follows a t-distribution with n - 1 degrees of freedom.

- Determine the critical value by finding the value of the known distribution of the test statistic such that the probability of making a Type I error — which is denoted \(\alpha\) (greek letter "alpha") and is called the "significance level of the test" — is small (typically 0.01, 0.05, or 0.10).

- Compare the test statistic to the critical value. If the test statistic is more extreme in the direction of the alternative than the critical value, reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. If the test statistic is less extreme than the critical value, do not reject the null hypothesis.

Example S.3.1.1

Mean GPA

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose we take a random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics. Since n = 15, our test statistic t* has n - 1 = 14 degrees of freedom. Also, suppose we set our significance level α at 0.05 so that we have only a 5% chance of making a Type I error.

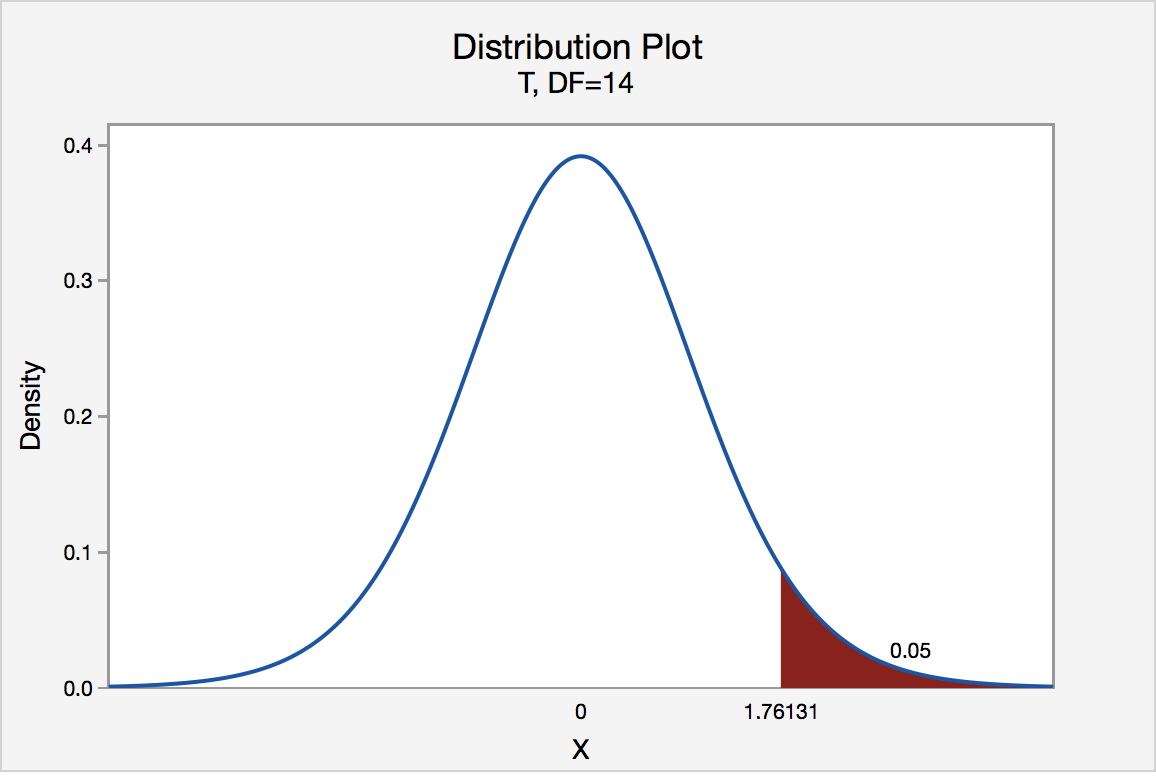

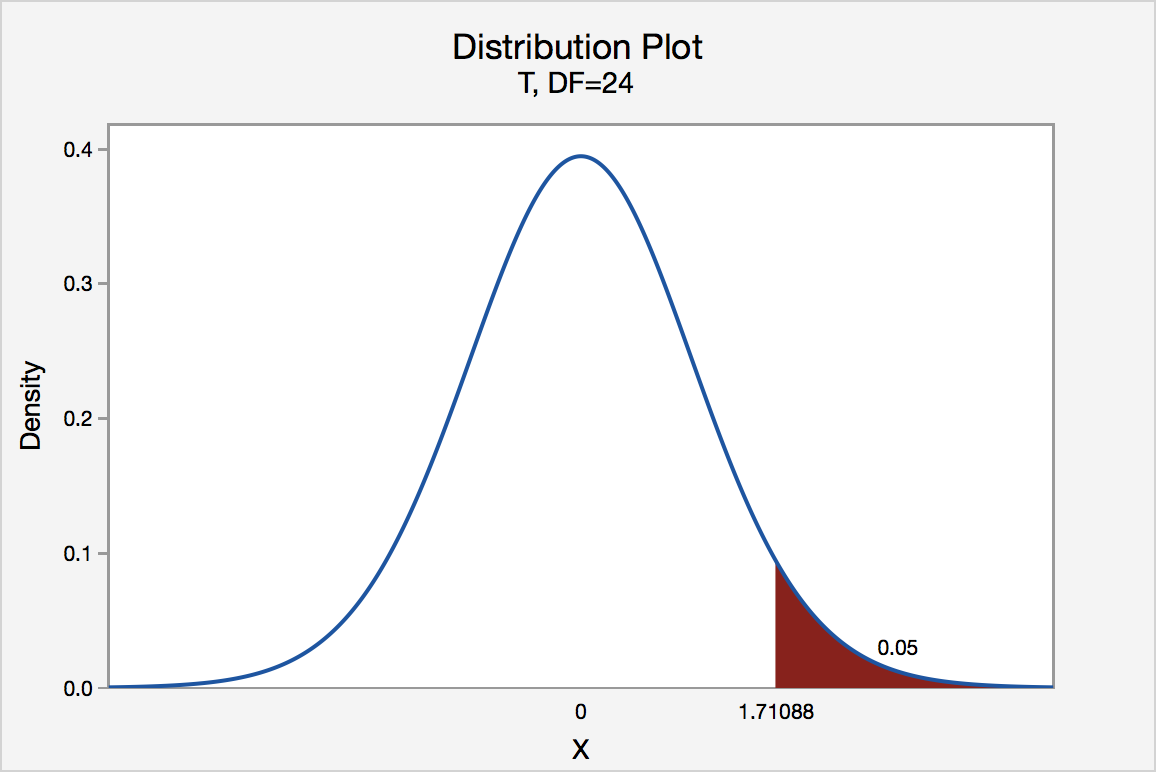

Right-Tailed

The critical value for conducting the right-tailed test H0 : μ = 3 versus HA : μ > 3 is the t-value, denoted t\(\alpha\), n - 1, such that the probability to the right of it is \(\alpha\). It can be shown using either statistical software or a t-table that the critical value t 0.05,14 is 1.7613. That is, we would reject the null hypothesis H0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis HA : μ > 3 if the test statistic t* is greater than 1.7613. Visually, the rejection region is shaded red in the graph.

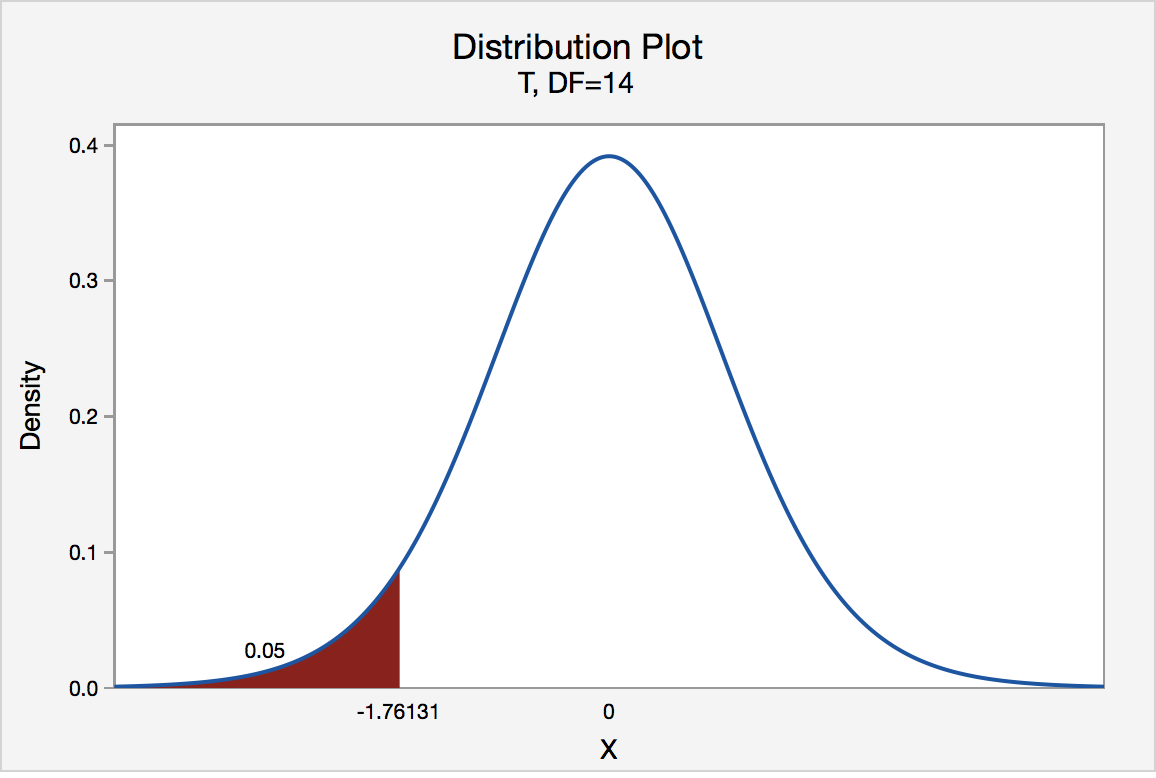

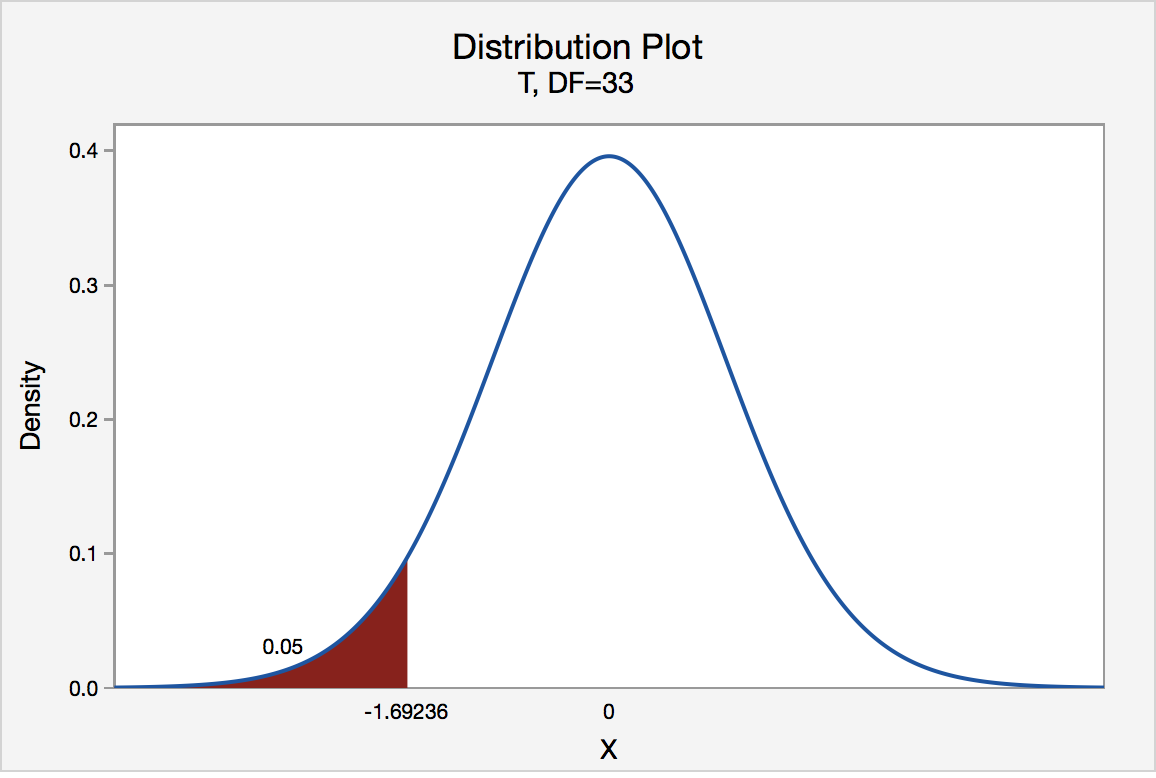

Left-Tailed

The critical value for conducting the left-tailed test H0 : μ = 3 versus HA : μ < 3 is the t-value, denoted -t(\(\alpha\), n - 1), such that the probability to the left of it is \(\alpha\). It can be shown using either statistical software or a t-table that the critical value -t0.05,14 is -1.7613. That is, we would reject the null hypothesis H0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis HA : μ < 3 if the test statistic t* is less than -1.7613. Visually, the rejection region is shaded red in the graph.

Two-Tailed

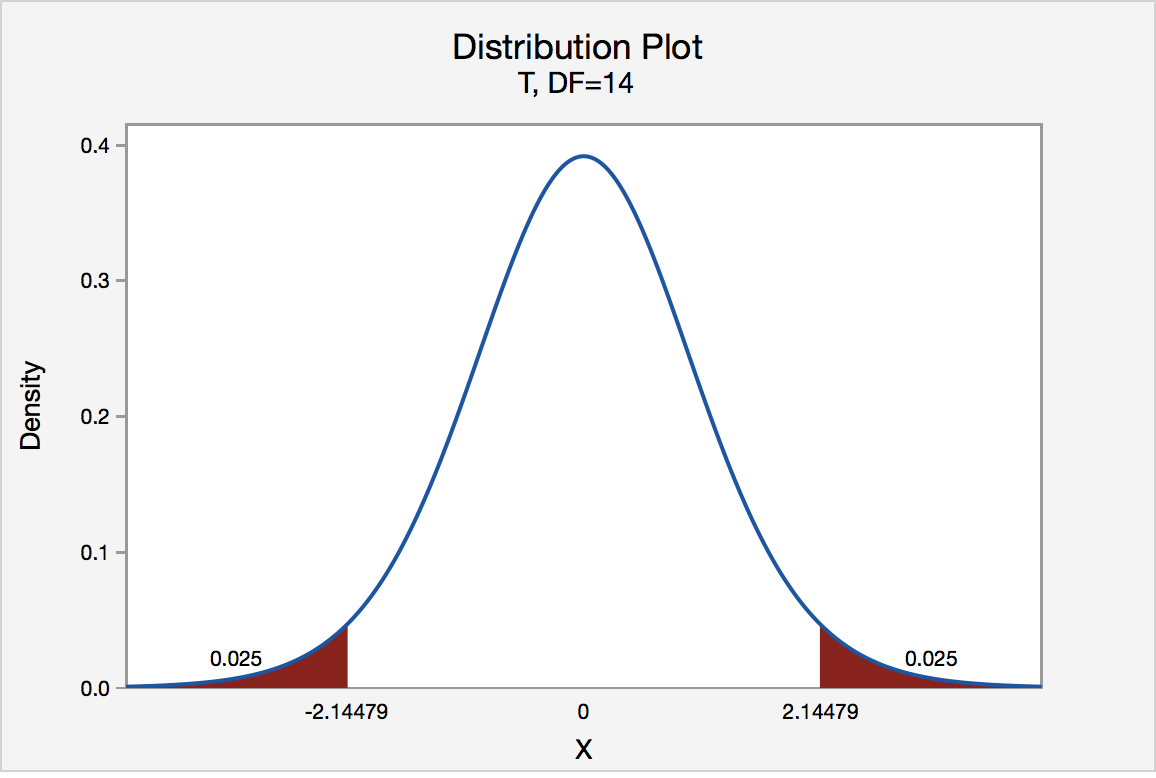

There are two critical values for the two-tailed test H0 : μ = 3 versus HA : μ ≠ 3 — one for the left-tail denoted -t(\(\alpha\)/2, n - 1) and one for the right-tail denoted t(\(\alpha\)/2, n - 1). The value -t(\(\alpha\)/2, n - 1) is the t-value such that the probability to the left of it is \(\alpha\)/2, and the value t(\(\alpha\)/2, n - 1) is the t-value such that the probability to the right of it is \(\alpha\)/2. It can be shown using either statistical software or a t-table that the critical value -t0.025,14 is -2.1448 and the critical value t0.025,14 is 2.1448. That is, we would reject the null hypothesis H0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis HA : μ ≠ 3 if the test statistic t* is less than -2.1448 or greater than 2.1448. Visually, the rejection region is shaded red in the graph.

S.3.2 Hypothesis Testing (P-Value Approach)

S.3.2 Hypothesis Testing (P-Value Approach)The P-value approach involves determining "likely" or "unlikely" by determining the probability — assuming the null hypothesis was true — of observing a more extreme test statistic in the direction of the alternative hypothesis than the one observed. If the P-value is small, say less than (or equal to) \(\alpha\), then it is "unlikely." And, if the P-value is large, say more than \(\alpha\), then it is "likely."

If the P-value is less than (or equal to) \(\alpha\), then the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis. And, if the P-value is greater than \(\alpha\), then the null hypothesis is not rejected.

Specifically, the four steps involved in using the P-value approach to conducting any hypothesis test are:

- Specify the null and alternative hypotheses.

- Using the sample data and assuming the null hypothesis is true, calculate the value of the test statistic. Again, to conduct the hypothesis test for the population mean μ, we use the t-statistic \(t^*=\frac{\bar{x}-\mu}{s/\sqrt{n}}\) which follows a t-distribution with n - 1 degrees of freedom.

- Using the known distribution of the test statistic, calculate the P-value: "If the null hypothesis is true, what is the probability that we'd observe a more extreme test statistic in the direction of the alternative hypothesis than we did?" (Note how this question is equivalent to the question answered in criminal trials: "If the defendant is innocent, what is the chance that we'd observe such extreme criminal evidence?")

- Set the significance level, \(\alpha\), the probability of making a Type I error to be small — 0.01, 0.05, or 0.10. Compare the P-value to \(\alpha\). If the P-value is less than (or equal to) \(\alpha\), reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. If the P-value is greater than \(\alpha\), do not reject the null hypothesis.

Example S.3.2.1

Mean GPA

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose that our random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics yields a test statistic t* equaling 2.5. Since n = 15, our test statistic t* has n - 1 = 14 degrees of freedom. Also, suppose we set our significance level α at 0.05 so that we have only a 5% chance of making a Type I error.

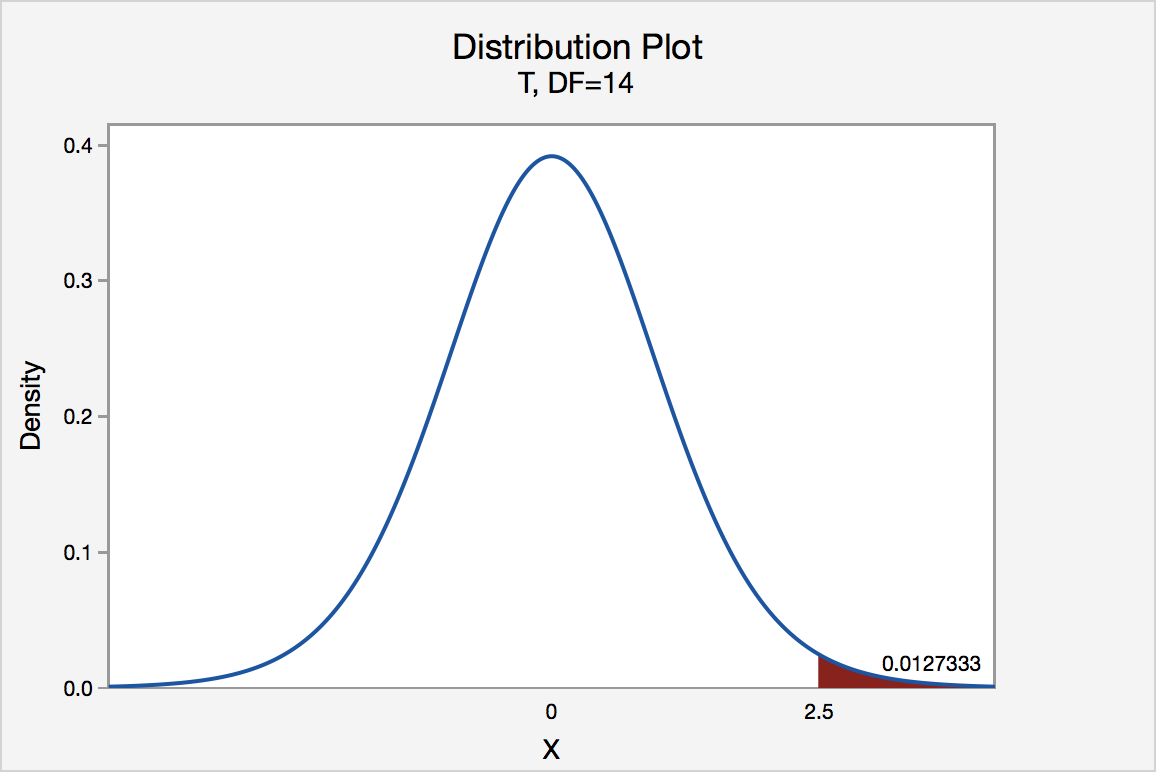

Right Tailed

The P-value for conducting the right-tailed test H0 : μ = 3 versus HA : μ > 3 is the probability that we would observe a test statistic greater than t* = 2.5 if the population mean \(\mu\) really were 3. Recall that probability equals the area under the probability curve. The P-value is therefore the area under a tn - 1 = t14 curve and to the right of the test statistic t* = 2.5. It can be shown using statistical software that the P-value is 0.0127. The graph depicts this visually.

The P-value, 0.0127, tells us it is "unlikely" that we would observe such an extreme test statistic t* in the direction of HA if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, our initial assumption that the null hypothesis is true must be incorrect. That is, since the P-value, 0.0127, is less than \(\alpha\) = 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis HA : μ > 3.

Note that we would not reject H0 : μ = 3 in favor of HA : μ > 3 if we lowered our willingness to make a Type I error to \(\alpha\) = 0.01 instead, as the P-value, 0.0127, is then greater than \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

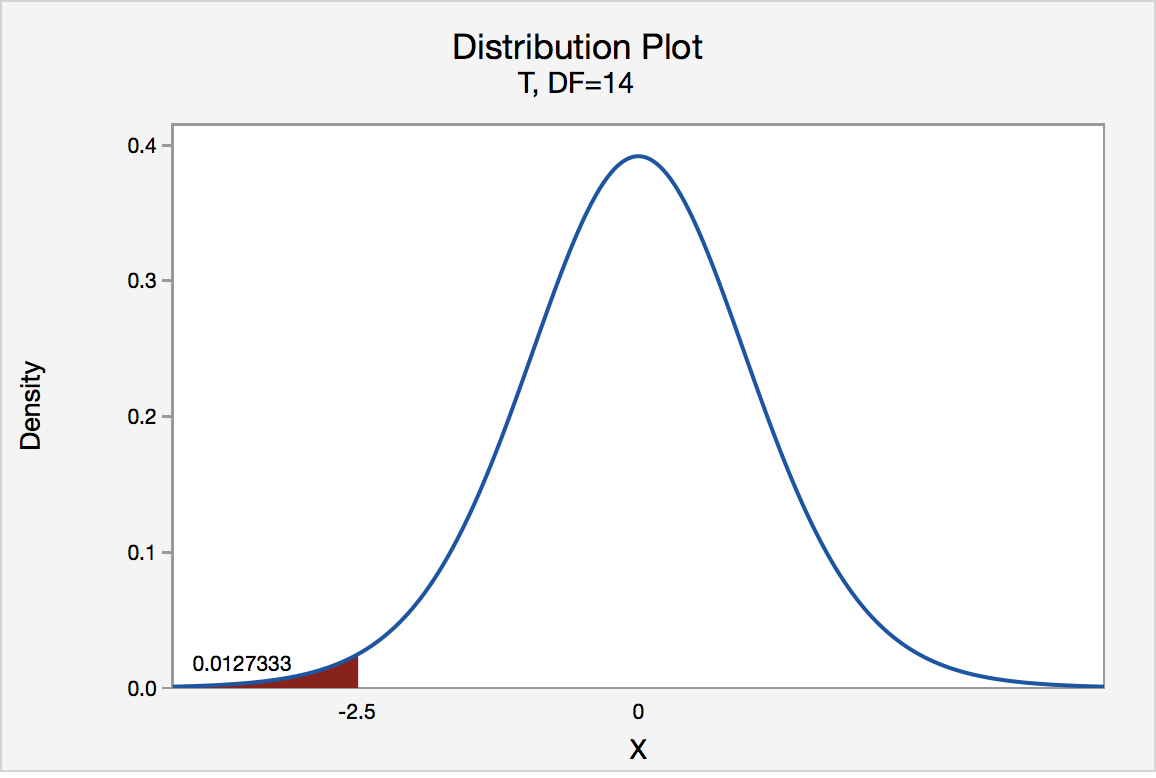

Left Tailed

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose that our random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics yields a test statistic t* instead of equaling -2.5. The P-value for conducting the left-tailed test H0 : μ = 3 versus HA : μ < 3 is the probability that we would observe a test statistic less than t* = -2.5 if the population mean μ really were 3. The P-value is therefore the area under a tn - 1 = t14 curve and to the left of the test statistic t* = -2.5. It can be shown using statistical software that the P-value is 0.0127. The graph depicts this visually.

The P-value, 0.0127, tells us it is "unlikely" that we would observe such an extreme test statistic t* in the direction of HA if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, our initial assumption that the null hypothesis is true must be incorrect. That is, since the P-value, 0.0127, is less than α = 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis HA : μ < 3.

Note that we would not reject H0 : μ = 3 in favor of HA : μ < 3 if we lowered our willingness to make a Type I error to α = 0.01 instead, as the P-value, 0.0127, is then greater than \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

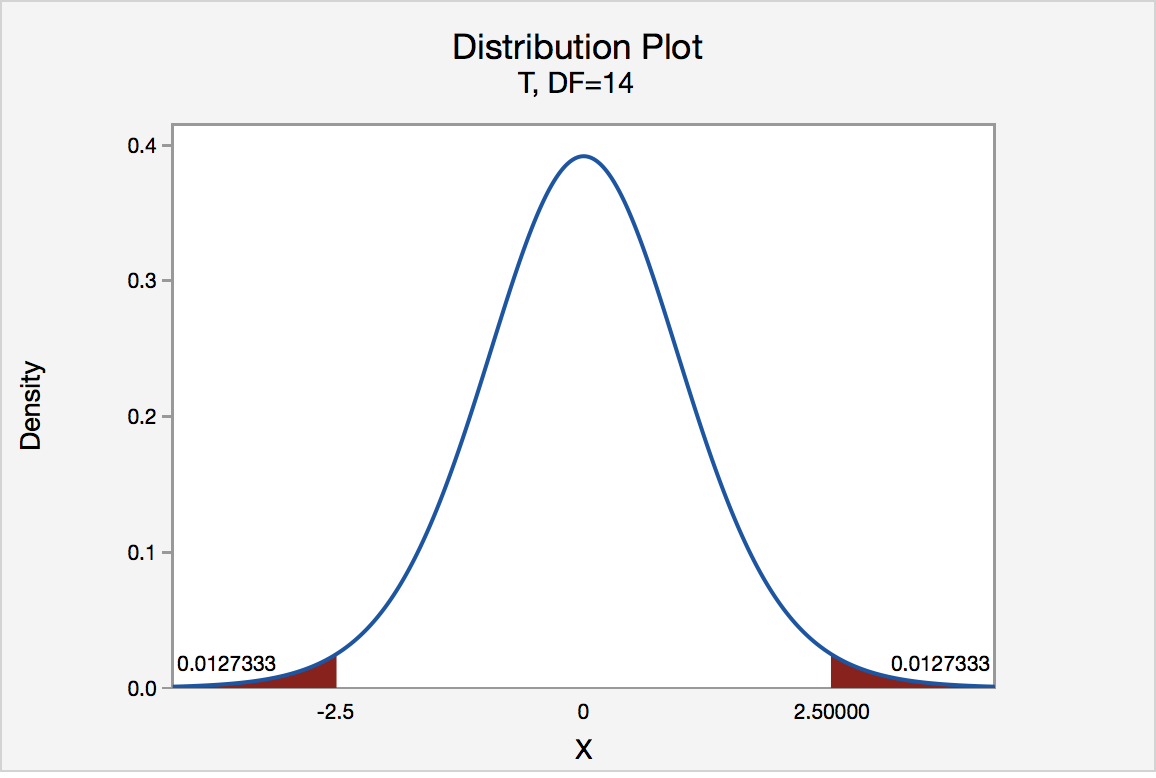

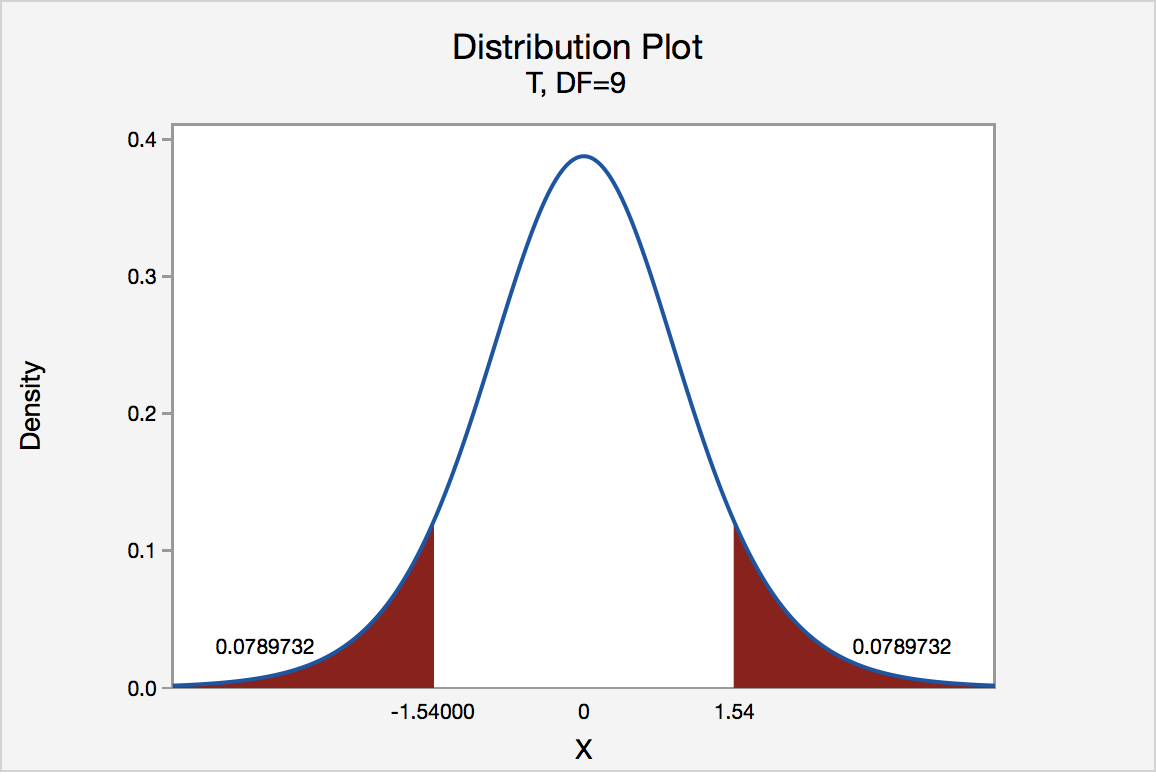

Two-Tailed

In our example concerning the mean grade point average, suppose again that our random sample of n = 15 students majoring in mathematics yields a test statistic t* instead of equaling -2.5. The P-value for conducting the two-tailed test H0 : μ = 3 versus HA : μ ≠ 3 is the probability that we would observe a test statistic less than -2.5 or greater than 2.5 if the population mean μ really was 3. That is, the two-tailed test requires taking into account the possibility that the test statistic could fall into either tail (hence the name "two-tailed" test). The P-value is, therefore, the area under a tn - 1 = t14 curve to the left of -2.5 and to the right of 2.5. It can be shown using statistical software that the P-value is 0.0127 + 0.0127, or 0.0254. The graph depicts this visually.

Note that the P-value for a two-tailed test is always two times the P-value for either of the one-tailed tests. The P-value, 0.0254, tells us it is "unlikely" that we would observe such an extreme test statistic t* in the direction of HA if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, our initial assumption that the null hypothesis is true must be incorrect. That is, since the P-value, 0.0254, is less than α = 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis H0 : μ = 3 in favor of the alternative hypothesis HA : μ ≠ 3.

Note that we would not reject H0 : μ = 3 in favor of HA : μ ≠ 3 if we lowered our willingness to make a Type I error to α = 0.01 instead, as the P-value, 0.0254, is then greater than \(\alpha\) = 0.01.

Now that we have reviewed the critical value and P-value approach procedures for each of the three possible hypotheses, let's look at three new examples — one of a right-tailed test, one of a left-tailed test, and one of a two-tailed test.

The good news is that, whenever possible, we will take advantage of the test statistics and P-values reported in statistical software, such as Minitab, to conduct our hypothesis tests in this course.

S.3.3 Hypothesis Testing Examples

S.3.3 Hypothesis Testing ExamplesBrinell Hardness Scores

An engineer measured the Brinell hardness of 25 pieces of ductile iron that were subcritically annealed. The resulting data were:

| Brinell Hardness of 25 Pieces of Ductile Iron | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170 | 167 | 174 | 179 | 179 | 187 | 179 | 183 | 179 |

| 156 | 163 | 156 | 187 | 156 | 167 | 156 | 174 | 170 |

| 183 | 179 | 174 | 179 | 170 | 159 | 187 | ||

The engineer hypothesized that the mean Brinell hardness of all such ductile iron pieces is greater than 170. Therefore, he was interested in testing the hypotheses:

H0 : μ = 170

HA : μ > 170

The engineer entered his data into Minitab and requested that the "one-sample t-test" be conducted for the above hypotheses. He obtained the following output:

Descriptive Statistics

| N | Mean | StDev | SE Mean | 95% Lower Bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 172.52 | 10.31 | 2.06 | 168.99 |

$\mu$: mean of Brinelli

Test

Null hypothesis H₀: $\mu$ = 170

Alternative hypothesis H₁: $\mu$ > 170

| T-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|

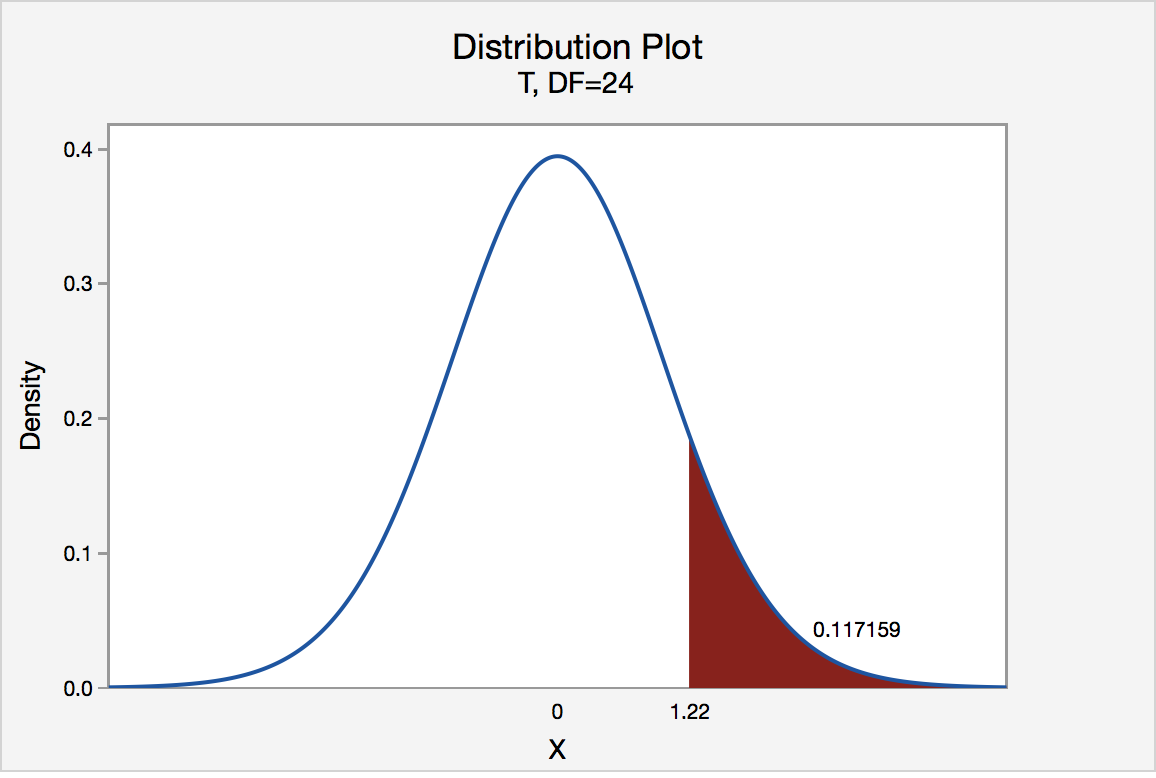

| 1.22 | 0.117 |

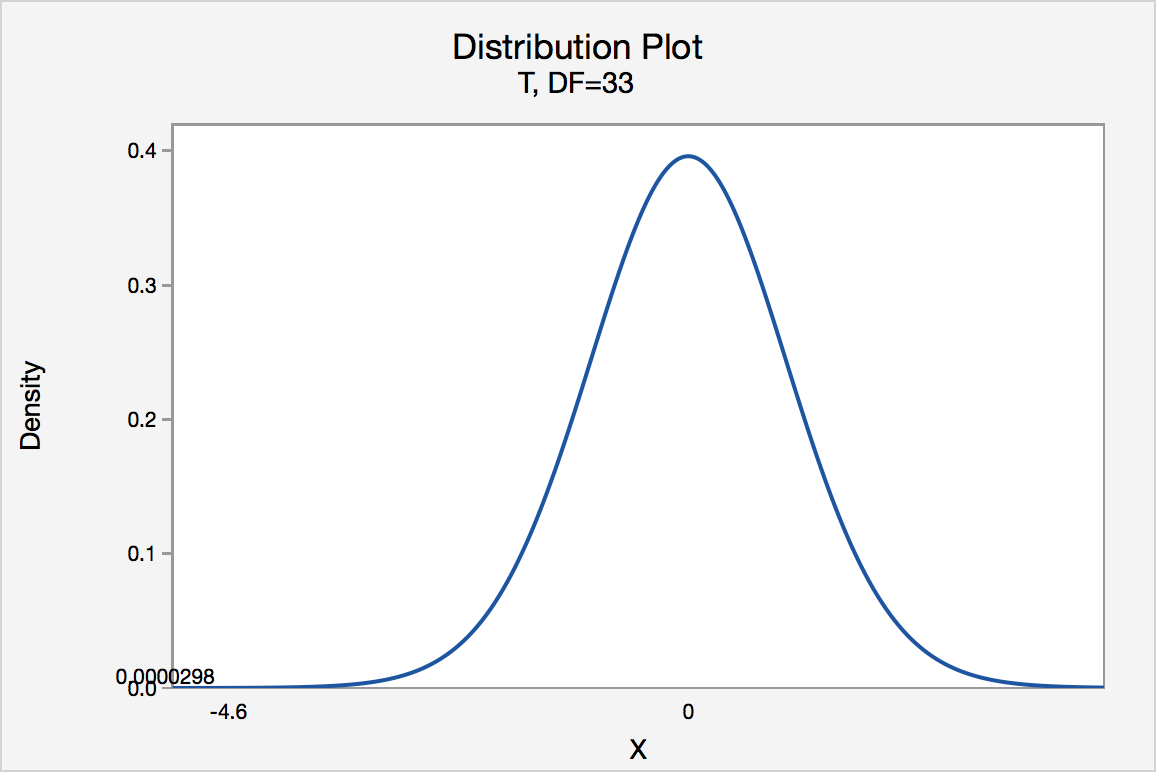

The output tells us that the average Brinell hardness of the n = 25 pieces of ductile iron was 172.52 with a standard deviation of 10.31. (The standard error of the mean "SE Mean", calculated by dividing the standard deviation 10.31 by the square root of n = 25, is 2.06). The test statistic t* is 1.22, and the P-value is 0.117.

If the engineer set his significance level α at 0.05 and used the critical value approach to conduct his hypothesis test, he would reject the null hypothesis if his test statistic t* were greater than 1.7109 (determined using statistical software or a t-table):

Since the engineer's test statistic, t* = 1.22, is not greater than 1.7109, the engineer fails to reject the null hypothesis. That is, the test statistic does not fall in the "critical region." There is insufficient evidence, at the \(\alpha\) = 0.05 level, to conclude that the mean Brinell hardness of all such ductile iron pieces is greater than 170.